Philadelphia WFL

Bell

- 1974 - 75

Waller’s staff was a mix of abilities and

personalities. Nick Cutro looked like a Jersey tough guy who had been through

the mill and his years as a minor football league coach and NFL scout had

toughened him for the ordeal of the Bell. Joe Gardi had a Maryland connection

with Waller as did Bob Pellegrini although the latter was remembered more for

his successful career as a ten year linebacker with the hometown Eagles and

Redskins. Gardi was somewhat unknown at the time but had been a high school

great in New Jersey, being named to the Newark Star-Ledger’s All Decade Team of

the 1950s as a Harrison High School star. He later went on to coach the N.Y.

Jets as an assistant, worked in the NFL office as a supervisor of officials, and

then returned to the sidelines as the long time coach at Long Island’s Hofstra

University, taking them from Division III status to their current position in

the Division IAA Atlantic 10 Conference. Defensive backfield coach Andy Nelson

had come off of the championship Colts teams as an All Pro and former offensive

linemen Ernie Wright had played with Waller on the 1960 LA Chargers and then for

him with the San Diego Chargers. It was a good staff. They had to go out and

find the players.

With former All Big Ten Wisconsin star Alan

“A-Train” Thompson coming into camp as what they thought would be their feature

back, the Bell could not know that he would be no more than a very capable

back-up. In Claude Watts they had the ultimate minor league football player. Ten

years that took him through the United Football League, Continental Football

League, and the Atlantic Coast Football League, Watts was a running back that

was just too good to hang them up and didn’t want to, yet never moved past being

briefly rostered by the K.C. Chiefs and had a short stint with the Winnipeg Blue

Bombers. Interestingly, Watts’ Bell backfield mate was John Land who it could

have been said, was “Waller’s Boy” in the most positive sense of the expression.

Land had left the Baltimore Colts in their 1968 Super Bowl year and played on a

succession of minor league teams, five years’ worth under Head Coach Waller.

Thus with other, younger, better known backs in camp, the Bell opened the season

with two thirty-year old running backs whose greatest triumph had been with the

ACFL’s Pottstown Firebirds where both formed that starting backfield. Another

Firebird grad who had a bit more pedigree than some of his Bell mates was the

quarterback, James Patrick “King” Corcoran, sometimes known as James Sean

(having added “Sean” himself to sound more Irish), often referred to as merely

“The King” and yes, everyone who knew the least bit about minor league football

knew King. Listed as a “rookie” quarterback for Tom Nugent’s 1962 University Of

Maryland team, the notation that the loss of “alternate QB Corcoran” going into

the 1963 season can only be interpreted that his career did not extend to

fruition in college. He was however, the undisputed king of minor league ball

with a presence and charisma that had to be seen and experienced. His leadership

skills pushed his teammates towards victory, a somewhat hidden trait that more

than overshadowed the two-game NFL experience he had with the Patriots, time in

camp with the Broncos, and a stint on the 1967 Jets’ taxi squad where he was

described as “the poor man’s Joe Namath” for his brashness and wardrobe. The

King had one more try with the NFL, this time with the Eagles, being released in

August of 1971. This “minor league backfield” brought the Bell the third highest

point production total in the WFL. The King was the number-two passer in the

league, runner-up to the Sun’s Tony Adams and he contended for years that if the

Bell had played their final game, one forfeited by the Chicago Fire, he could

have led the league in passing. Both Watts and Land were ranked in the top seven

in both scoring and rushing. Throw in the second best punt returner (Ron Mabra)

and the number six kickoff return man (Jimmie Joe, younger brother of former Jet

and Bronco Billy Joe) and “potent” could be spelled with capital letters! If one

wanted to find a reason to watch WFL football and cheer for the underdog,

offensive tackle and guard Bill Ellenbogen could have been held up as a standard

case study. He started his college career at the University Of Buffalo and

transferred to Virginia Tech. He was the last player cut by Hank Stram from the

1973 Chiefs and played with the semi-pro Albany Metro Maulers. When the NFL

players called their strike in 1974, Ellenbogen traveled to the Oilers camp and

did not object to being given number sixty-five. He was after all, an offensive

guard and sixty-five was an appropriate number for his position. When the

striking regulars agreed to return to camp, the Oilers’ “real” number

sixty-five, perennial All-Pro Elvin Bethea was incensed that someone else had

worn his number and had done it as a strike-breaking scab. Bethea threatened

Ellenbogen and then made good on the threat, delivering a stunning roundhouse

punch in a team scrimmage. Released by Houston, Ellenbogen’s next stop was with

the Bell of the WFL where he played out the ’74 season. In 1975 he did not wish

to face the financial uncertainty of the New League WFL and was invited to the

Redskins camp by George Allen. Again finding himself the last man cut from the

team, it was back to the WFL, this time with the Shreveport Steamer. When the

league folded, Ellenberger waited until 1976 before trying out with the Giants

but they cut him. He then traveled to Winnepeg of the CFL and made the squad.

When injuries crippled the Giants offensive line after the second NFL game of

the season, he was called back to the Giants and lasted the season and then

through 1977 as well. These were the typical men of the WFL. The only knock on

the offense was its inconsistency and Waller’s tendency to call plays as if he

was a riverboat gambler.

The defense unfortunately was a bit more porous

with defensive back Mabra the standout performer. Stuffing the run was the

province of strongman Tom Laputka who had been named MVP in the 1973 Grey Cup

Game for the CFL championship. He teamed with Bob Grant, the middle linebacker

who had helped to take the Colts to the 1968 and 1970 Super Bowls. There just

wasn’t a lot of talent besides them on the defensive side of the ball. Laputka

played gleefully due to a landmark legal decision. As a true star-on-the-rise

with Ottawa in the CFL, Laputka was still quick to jump to the Bell and take the

opportunity to play close to his New Jersey hometown outside of Philadelphia.

The CFL sued the WFL over this breach of contract issue and won compensation for

Laputka but one of the final stipulations was that Tom receive his Bell salary

“up front” which proved to be fortunate. Laputka was one of the few who managed

to collect his entire annual salary, and returned to Canada for another two

years of productive play at the conclusion of the 1974 season. Two other

defensive players of note to join the Bell were Steve Chomyszak and Tim

Rossovich. Rossovich was known as a wild-eyed defensive end, and later, middle

linebacker who starred with the Eagles until his antics became such that he was

moved on to the Chargers. His bodyweight had dropped so low that some coaches

speculated that he was playing at little more than 200 pounds, forcing his

release. As a Philly fan favorite, he was a natural for the Bell. Although

better known for lighting himself on fire and eating glass, Rossovich could

still make some game-changing plays. He later used his derring-do attitude and

seemingly endless tolerance for pain for a career in Hollywood as a stunt man

and actor. Chomyszak was not as well known but had the reputation of being one

of the strongest men to ever play in the NFL. He was considered to be an Olympic

level shotputter after only one year of competition at Syracuse, tossing the

shot over 65 feet. Former Bengal strength coach Kim Wood stated that Chomyszak

could squat 800 pounds, deadlift 800 pounds, and bench press over 500 pounds at

a time when these were close to world record lifts and he did this with the

leverage disadvantage of being 6’7” tall. After retiring from football, the

quiet and reserved Chomyszak, whom some coaches felt needed a bit more “killer

instinct” to match his prodigious strength, made millions of dollars in the coal

industry but died from liver and pancreatic cancer before truly enjoying the

money he had made. Burly Rick Cash was another defensive end, nicknamed

“Thumper” for the obvious reason of having the ability to crack opponents into

next week. Originally drafted by the Packers in 1968, he was released but then

played with Atlanta, the Rams, and the Patriots in a six year NFL career. Not

yet ready to quit, he joined the Bell and earned a reputation as one of

Rossovich’s henchmen. On one occasion, Rossovich didn’t like the particular tee

shirt given to him by equipment man Bob Colonna so he and Cash threw Colonna

into a garbage can, taped the lid on, and rolled it around the locker room to

uproarious laughter. One special teams standout who doubled at wide receiver

proved to be as exciting as Mabra. “Forgetting” to play college football, Vince

Papale instead captained the St. Joseph College track team and parlayed his

experience at Interboro High School and with the Seaboard League’s Aston Knights

into a starting position. Demonstrating that Waller’s decision to keep and later

start Papale was no fluke, Vince became known for his grit and determination as

a special teams wildman with the Philadelphia Eagles from 1976 through 1978.

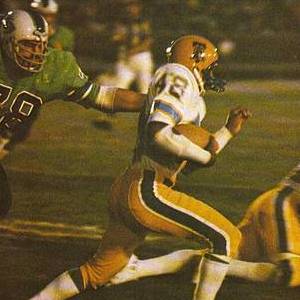

The Bell uniforms may be better known than some of

the other World Football League teams. NFL Films did a nice feature on the WFL a

few years ago as part of their LOST TREASURES OF THE NFL series and interviews

with King Corcoran’s son Jimmy and film clips of the Bell were prominently

featured. Theirs was a great jersey in a striking shade of “blue” augmented by

yellow/gold and white trim. HELMET HUT has for a very long time, featured the

King Corcoran Bell helmet on the WFL area of the site. The “off” yellow color

reminds many of the Sunflower Gold used on some teams’ helmets and the

contrasting stripes and distinctive Philadelphia Bell with its characteristic

crack is an iconic symbol of this team. Many of the Bell players wore

contrasting royal blue Dungard masks that gave the helmet an excellent and

“clean” look that many collectors covet to this day. IN 1975... The financial collapse of

the World Football League exposed a number of owners as frauds, others of being

guilty of making a poor business decision, and some as the legitimate

behind-the-scenes financers. In Philadelphia the venerated Kelly family had

their name on the ownership papers and the respect and fondness for this

long-established family helped pave the way for concessions from the City.

However, those on the inside knew that while the name was sound, the bankbook no

longer was. As the fiasco of 1974 moved forward, John Bosacco came out from the

shadows and not only revealed himself as the deep pockets of the franchise but

someone who believed that the league could be salvaged. Working closely with

Chris Hemmeter, Bosacco helped to remove 1974 Commissioner Gary Davidson from

power, install Hemmeter, and then make plans that would lead to the formation of

the New League, Inc., DBA The World Football League for 1975. Bosacco stayed in

the league’s front office as acting secretary and a member of the Executive

Committee. A successful attorney and MBA, Bosacco believed his Bell team had the

goods to go all the way. One of the front office changes was removing Ron Waller

as General Manager and giving him head coaching responsibilities only. In

Waller’s defense, he had but sixty days to assemble a staff and team after being

hired for both positions in 1974. There were problems with vendors, office

staff, and general business matters often due to an incomplete or absence of

communication among departments. Bosacco believed that naming 1974 Bell business

manager Richard Iannarella as GM and allowing him to take care of the “business

end” of the Bell including player contracts, would allow Waller to focus on

coaching only. Waller’s 9-11 record was seen as an underachievement by some as

he had a lot of high-powered offensive talent, thus unburdened of his front

office responsibilities, it was expected that he would post an improved record.

Six-time All Pro and former Green Bay great Willie Wood was hired as the

Assistant Head Coach and defensive coordinator. Former L.A. Rams great Duane

Putnam, a three-time All Pro guard was brought in to handle the defensive line.

Joe Gardi, the Bell offensive backfield coach the year before, was retained to

handle the offensive line. Like Waller, Gardi had been an outstanding player at

Maryland. Joe Gaval, a Bell scout, moved into the coaching suite to take on the

special teams assignment. It was expected that Wood’s experience and talent

would help to improve the defense and that Waller’s wide-open, gambling, big

play offense would be more consistent. They averaged thirty points per game in

1974 but that average resulted from unpredictable and inconsistent performances.

The Bell came into 1975 with

what appeared to be the best rushing attack in the league. While the media was

hyping the Memphis combination of the highly paid Larry Csonka and Jim Kiick,

some of the more sophisticated observers were quick to note that the Bell’s John

Land and Claude Watts accounted for over 2000 yards in 1974. The scourge of the

best of the minor football leagues in the late 1960s, Land and Watts

complemented each other magnificently and between them, could run, block, and

catch with the best. Adding the Southmen’s J.J. Jennings who ran for over 1500

yards in ’74 made this a potential blockbuster backfield. Philadelphia was

closer to Jennings’ Massachusetts home than Memphis, so happy with his entry

onto the Bell squad, high hopes were present for this backfield. As a star at

Rutgers and the country’s leading collegiate scorer, the Bell might have thought

he could also bring in more fans. Wisconsin’s Alan “A-Train” Thompson joined the

squad during the 1974 season and despite an enviable collegiate record,

contributed minimally as he would in ’75. An attempt was made to upgrade the

receiving corps with NFL super star Ted Kwalick and Eagle mainstay Ben Hawkins,

on paper certainly, a tremendous improvement from 1974’s group. Hawkins was a

Philly fan favorite, a starter since joining the Eagles in 1966 and he led all

NFL receivers in reception yardage in ’67. His broken leg in 1973 made him

expendable and he was traded to the Browns for the 1974 season, joining the Bell

in ’75. Kwalick was one of the ballyhooed 1974 futures that the WFL bragged

about. Like Csonka, Kiick, Warfield, Lamonica, and Stabler it was a player of

Kwalick’s stature that they felt would give the league credibility and attract

other disgruntled NFL regulars. Originally signed as a future with the

Hawaiians, Kwalick was “dispersed” to the Bell in the league’s attempt to

achieve more competitive balance as they approached the 1975 season. Kwalick was

a genuine All Pro, three times over in fact and was considered one of the top

two or three tight ends in the game. He was also versatile and was sometimes

used as a wide receiver and what later was referred to as the “H-Back” in the

49er offensive scheme. A two-time All American out of Penn State and a former

All State athlete at McKees Rock, PA Montour High School, Kwalick was considered

to be “hometown” to Philly fans despite growing up in the Pittsburgh area. None

of the Bell receivers were among the top statistical finishers but among

Kwalick, Hawkins, and running back Land they had almost ninety receptions and a

thousand receiving yards that made for a potent attack. Two of the lesser-known

receivers were back from the ’74 squad, small, less talented than the others,

but highly motivated. Vince Papale, the track star turned pro football player

who would go on to be a special teams demon for the Eagles continued his role as

fan favorite with his spirited special teams play. The other was Long Island

product Len Izzo, a 185 pound package of dynamite who had led what was then

called the small college division in kickoff returns his senior year at C.W.

Post College. Izzo did well with the Hartford Knights of the ACFL after failing

a free agent tryout with the Browns, and played with the Bell as a sometimes

starter for its two years. No longer directing the attack was “King” Corcoran,

the team leader who had headed the Bell in every one of their 1974 games.

Corcoran finished ‘75 by completing less than fifty percent of the passes he

threw but he wasn’t called upon to shoulder the load as he was in ’74. Instead,

World Bowl quarterback Bob Davis who had enjoyed a seven-year pro career with

three teams and who led the Blazers in 1974 was the Bell regular. A New Jersey

native, he was thrilled to be playing so much closer to home especially since he

had a strong involvement with a number of charitable and community organizations

in his home town of Monmouth. Defensively, some of the

bigger names were still there but for the Bell this unit was never its strong

point. The Defensive Player Of The Year in Northern California at St. Francis

H.S. of Mountain View was Tim Rossovich who still had a huge following in

Philadelphia. He started all but one game for the Eagles in a four-year career

at both defensive end and middle linebacker. His antics of setting himself on

fire, eating glass, drinking motor oil, and being the life of every party

endeared him to Eagle fanatics. His off-season “job” of making sand candles and

lounging on the beaches of his home state made him a counter-culture hero, the

look complete with a blowout Afro hairstyle that was barely contained within the

confines of his helmet. That he hit a ton when he came to play put him in the

1969 Pro Bowl but a loss of bodyweight, strength, and the quickness that had

made him a special player as the leader of USC’s Wild Bunch had him starting

most of the Bell games in 1974 and ‘75, instead of playing in the NFL. Louis

Ross who had played so well for the Blazers the year before, had his pick of

suitors and chose the Bell when the Blazers went bankrupt. Originally a

basketball player at South Carolina State, he was an early advocate of Nautilus

training which boosted his muscular bodyweight by more than thirty pounds and

gave him significant strength to augment his great speed and reaction. An eighth

round choice of the Bills, he was a 6’7” special teams player who was later

traded to Atlanta and the Chargers before hooking up with the Blazers which gave

him the opportunity to play in front of his home town crowd. When the WFL

finally ceased operation, he continued his career in the Canadian Football

League. Rookie middle linebacker Steve “Rocky” Colavito out of Wake Forest was a

genuine find. A Bronx boy from New York City, he played at traditional Catholic

School League powerhouse Cardinal Hayes before embarking for Wesley Junior

College of Delaware and then Wake Forest. Colavito came by his nickname the

honest way as a cousin of Detroit baseball great Rocky Colavito and he was a

rock! At 6’ and 225 pounds he was considered a bit undersized starring at Wake

Forest but did get a shot with the N.Y. Jets. Failing that he moved on to the

Bell for 1975 and was their outstanding rookie and an immediate starter. When

the season ended prematurely, he hooked on with the Eagles for their final games

of the ’75 season. When Willie Wood moved Rossovich from linebacker to the

defensive end spot that first earned him so much acclaim, the Bell defense

looked to be improved over 1974. Philadelphia Bell expert Tom

Heffner who maintains an internet site that provides a tremendous amount of

information about the Bell and their history (http://www.geocities.com/wflphiladelphiabell)

noted that the chaos that engulfed the World Football League from its inception

also affected the Bell that had been one of the few franchises that seemed to

have a modicum of stability. By the time the team took the field for its July 27th

pre-season game against the Portland Thunder, Waller and most of the staff had

been fired and Joe Gardi was elevated to Interim Head Coach, with King Corcoran

directing the offense. After the game, yet another move was made and the shakeup

in the coaching staff elevated Assistant To The Head Coach Willie Wood to the

top spot for the regular season opener against Hawaii on August 2nd.

The significance of this hire was that Wood was now the first African-American

to be the head coach of a professional football team. Wood’s road to the top had

been difficult. A product of the streets of Washington, D.C. Wood depended upon

Bill Butler, his Boys Club coach to write letters to USC in order to get their

attention and consideration for a scholarship. In an era when a Black

quarterback was a rarity, he led USC as their signal caller and defensive back.

He was passed over in the NFL draft and again called upon Butler to help make

contacts in the NFL. The Packers were the only team that responded and he

surprised the Lombardi staff by successfully competing against twenty-four other

defensive backs for a roster spot. Used almost exclusively on punt returns, Wood

did not blossom until 1961, his second year, starting in place of an injured

Jess Whittenton and leading the NFL in punt returns. From there, he had a Hall

Of Fame career with the Pack. Wood repeated his ground-breaking role when he

became the first African-American Head Coach in the Canadian Football League in

1980, with the Toronto Argos. Wood immediately brought coaches to the Bell who

looked like a mid-1960s NFL All Star team. Former Packer defensive backfield

teammate Herb Adderley took over the position as defensive backfield coach.

Adderley didn’t have to go far as he was a Philadelphia native, a graduate of

Philly’s Northeast High School, and a restaurateur in town. Former Steeler, Ram

and Redskin great linebacker Myron Pottios, a western Pennsylvania legend who

also starred at Notre Dame was rushed in to coach the defensive line. Ex-Browns

running back Leroy Kelly, another Philadelphia high school star out of Simon

Gratz H.S. and then Morgan State, had finished his playing career with the

Chicago Fire and jumped at the chance to coach the Bell’s stable of offensive

backs. Frank Gallagher who had starred on a number of excellent Detroit Lion

offensive lines had come into the Bell’s ’75 camp as a projected starter, a

tough, experienced player who would enhance the offensive line’s performance and

give it consistency. Gallagher was another Philly product having played at St.

James H.S. in Chester and Wood offered him the offensive line job. Wood

continued the staff overhaul a few weeks before the collapse of the season when

he added former Redskin head coach Bill McPeak, most recently laboring as Abe

Gibron’s right hand man in the brief life of the Chicago Winds. McPeak was hired

to direct the offense as coordinator. He immediately simplified Waller’s scheme

and put emphasis on the fundamentals rather than the multitude of offensive

formations that were favored by Waller. If the Bell had built an offensive

reputation for one thing, it was inconsistency. After ten games and a 3-7

record most of the offensive statistics were toward the bottom of the league

while the defense was carrying, or trying to carry the load. Rookie linebacker

Steve “Rocky” Colavito as an example had one hundred and thirty tackles

including seventeen solos and another eleven assists against Portland in a 25-10

loss. The Bell would complete the shortened season with a 4-7 mark and like the

remainder of the World League, faded into memory. The Bell uniforms were the

same as they were in 1974 with the immediately recognized cracked Liberty bell

and the beautiful blue and gold jerseys.