Here is a very interesting piece by guest blogger, John Freeman. Most of the articles on this site generate pleasant memories. Others insight moderately-heated debate among old fans, but all is done with a general love of the game or a team in-mind. This post may just make readers squirm a bit – it did me. However, the things that Freeman outlines here did occur, with the Chargers, and likely with other teams as well.

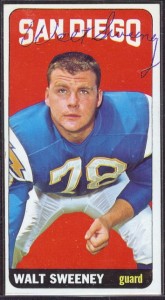

Similar to the players of earlier generations that are now suffering due to the inferior equipment they wore and a lack of knowledge about concussions and blows to the head, many have had to battle dependencies on drugs or PEDs that they were encouraged (or forced, depending on the situation) to use to maintain their position with a team. Walt Sweeney was one of the earliest and most vocal former players to call attention to the chemical use in professional football, and sports in-general.

By all accounts, Walt Sweeney was a fearsome football player who lived a wild, sloppy and undisciplined life.

His passing last month provides a fascinating connect-the-dots linkage through the decades in sports relating to the abuse of steroids, amphetamines and barbiturates and all manner of related performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs).

To put it into perspective: None of the many current-day drug abuse scandals by prominent athletes – most notably Lance Armstrong these days, but also the Hall of Fame rejections of McGuire, Sosa and Bonds, plus the on-going Miami-based sports clinic scandal – should be viewed as anything out of the ordinary in the world of high-performance sports.

Nor, for that matter, are they new.

Just as Junior Seau’s suicide has brought scrutiny and high-profile litigation to the NFL because of his prominence and the brain damage he suffered, so too should Sweeney’s death at age 71.

Sweeney proudly, wantonly abused both alcohol and drugs his entire life, but it was pill-form amphetamines, barbiturates and steroids that got him started when he was with the Chargers in the early ‘60s. Prior to the ’63 season, the Chargers hired pro football’s first “strength” coach, Alvin Roy, who brought the benefits of intense weight-lifting into pro football.

He also introduced a new, fast-acting and very effective steroid, taken in pill form, called Dianabol.

Dianabol pill-popping was rampant and made freely available by the team. Consumption was highly encouraged. Ron Mix has stated that 95 percent of the team freely took the pills. Unwritten team policy was that they pop Dianabol, as many pills and as often as they pleased. By the handful, every day, before and after each practice.

And why not? It made the Chargers stronger, faster, quicker and much angrier. What role did Dianabol have in the Chargers’ winning the AFL championship that season? A lot, no doubt.

San Diego’s proximity to Mexico, where these illegal drugs were (and still are) easily obtained made the region a haven for those Chargers, such as Sweeney, who sought other illegal substances beyond Dianabol.

Point is, Sweeney’s death is emblematic of a performance-enhancing drug-use craze among world-class athletes that, over the years, become a threat to the integrity of all sports. Illegal drug use (largely undetected) has become commonplace, despite better testing and stiffer penalties. Each year, pro football, baseball and basketball claim to have steroid abuse under control, but recent revelations in each sport – all sports, really, especially cycling – would indicate that’s hardly the case. Another crucial element of the story: Walt Sweeney was fully aware that steroids caused him to act crazier than he already was.

So he sued the NFL in 1995 – and won. The league was ordered to pay him $1.8 million in disability payments. Yet, by 1997 that judgment was overturned on appeal and he received what the NFL thought he deserved — absolutely nothing — much like dozens of other players who made similar claims against the league.

Now, of course, more than 3,800 former NFL players who joined forces to file a massive class-action suit against the NFL. Their claim is slightly different: Poor protection from violent collisions, resulting in measurable brain damage.

Yet, it wasn’t only the poorly designed helmets and repeated violent hits that caused such lasting brain damage. Using Walt Sweeney’s life and death as the latest example, it was drug abuse.

Based on rampant drug use throughout the ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s, ’90s and well into this century, you have to wonder how many ex-NFL and AFL players (and athletes in other sports) were adversely affected by a career-long abuse of their cocktails of choice — steroids, amphetamines and barbiturates.

How much were they encouraged to take those pills? And what did those in charge – coaches, league officials, team doctors – do about it?

Now that’s a story worth telling.