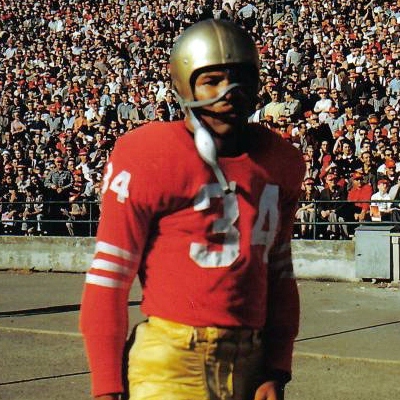

"The Absolutely Great Joe Perry"

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS May 2011:

THE ABSOLUTELY GREAT JOE PERRY

By Dr. Ken

For those of a certain age, our football experience as players and/or fans cuts across the Golden Age of Pro Football of the 1950’s and through the birth and subsequent absorption of the American Football League into the National Football League. By any standard of measure, the fifteen to twenty year period marked by the Fifties and Sixties was truly the very best of times for football. I would argue that the greatest players, the greatest games, the most significant of events that shaped the game and its place in our culture occurred in this time span and both ESPN and The NFL Network be damned. Their “Top X Number” lists are a joke, clearly chosen by individuals whose sense of football history goes back no further than 1965 and only then to pay homage only to the most obvious of great players. Watching these programs and the discussions about great players makes one feel as if their roundtable production meetings follow the path of “Well, we have to include Unitas somewhere on the list so let’s plunk him right about here and then get back to the Marinos and Bradys.” While there are certainly very good and a few great players on today’s field, far too many now entering the Pro Football Hall Of Fame more accurately belong in what the Pro Football Researchers Association refers to as “The Hall Of Very Good.” (allow me to note that the PFRA is definitely an organization you would want to join for a boatload of hard to find, wonderful information, see http://www.profootballresearchers.org/ ).

|

Too many of the truly great players of half a century ago have all but been forgotten and for those who witnessed his abilities, his deeds, and his influence Joe Perry certainly was one of these. As a member of The Pro Football Hall Of Fame perhaps most readers would think that he is far from forgotten but the magic that he brought to the field of play is not appreciated even by those who first became fans in the late 1960’s and early ‘70’s. His place in social history is certainly lost. Coincidental to my remarks in the preceding paragraph about the recently constructed “Best” lists, in the excellent book Gridiron Gauntlet; The Story Of The Men Who Integrated Pro Football, author Andy Piascik begins his chapter on Joe Perry with the following words:

“Whenever sports pundits talk about the greatest running backs of all time, it is rare that they mention Joe Perry. That is true even when the field is as large as ten, as in the Ten Best Running Backs or Ten Greatest Running Backs. Usually such lists go something like this: Jim Brown, Walter Payton, Barry Sanders, Emmitt Smith, Eric Dickerson, O.J. Simpson, Earl Campbell, Gale Sayers, Thurman Thomas, and Tony Dorsett. Because Joe is almost never on such lists, younger fans are likely to respond to a call for his inclusion by asking, Who the heck is Joe Perry? Well. Consider a few facts and then consider that the better question is, Why the heck isn’t Joe on these lists?”

|

|

An artist’s rendition of the mask worn by Joe Perry to protect a broken jaw sustained in the pre-season of 1954

Needless

to

add,

I

could

not

agree

more

and

as

the

first

Black

player

on

the

Forty

Niners,

he

certainly

was

a

ground

breaker

who

represented

all

the

best

qualities

of

an

athlete

and

man.

Born

in

Arkansas

but

raised

in

the

Compton

section

of

Los

Angeles,

Fletcher

Joseph

Perry

was

an

athletic

standout

at

David

Starr

Jordan

High

School,

starting

for

the

varsity

football

team

as a

thirteen

year

old.

Perhaps

it

could

be

stated

that

Perry

began

a

great

athletic

tradition

at

what

was

the

relatively

small

Jordan

High

School,

paving

the

way

for

Olympic

champions

and

world

record

holding

track

performers

Florence

Griffith-Joyner

and

Kevin

Young.

With

his

heart

set

on

attending

UCLA

so

that

he

could

follow

in

the

footsteps

of

his

idol

Kenny

Washington

and

with

the

academic

and

athletic

accomplishments

to

qualify,

he

was

snubbed

by

his

hometown

university.

As

USC

did

not

in

Perry’s

opinion,

seem

to

be

ready

for

Black

football

players,

he

chose

local

Compton

Junior

College

as

his

next

stop.

Future

Pro

Football

Hall

Of

Fame

San

Francisco

Forty

Niner

teammate

Hugh

McElhenny,

another

Los

Angeles

product,

also

played

there

before

embarking

on

his

All

American

career

at

Washington.

After

a

fine

first

season

on

the

field

and

in

the

classroom

as a

math

major,

Perry

enlisted

in

the

Navy

in

order

to

serve

his

country

during

the

Second

World

War.

He

later

noted

that

he

was

not

comfortable

with

the

term

“African-American”

to

describe

his

race.

He

was

clear

that

he

was

“an

American”

who

“served

America”

while

in

the

military.

When

he

returned

from

overseas

he

was

stationed

at

the

Alameda

Naval

Air

Station

where

his

football

exploits

attracted

both

the

NFL

Los

Angeles

Rams

and

the

All

American

Football

Conference

San

Francisco

Forty

Niners.

Though

the

Rams

offered

Joe

more

money,

he

chose

the

Niners

because

of

his

immediate

bond

with

their

owner

Tony

Morabito,

a

man

he

felt

was

like

a

second

father

to

him.

Despite

some

racial

prejudice

shown

towards

him

on

the

field,

Perry

always

was

clear

that

he

was

and

would

be

patient

with

those

who

spoke

badly

towards

him

but

would

not

tolerate

any

physical

punishment

because

of

his

race.

Though

his

49er

backfield

mate

in

later

years,

John

Henry

Johnson,

was

known

far

and

wide

as

perhaps

the

most

intimidating

player

in

the

pro

ranks,

Perry’s

reputation

as a

proud

man

who

would

retaliate

immediately

if

he

believed

his

physical

well

being

was

being

compromised

made

him

very

much

a

highly

respected

individual

among

his

teammates.

Both

Perry

and

other

Niners

of

the

team’s

early

years

stressed

constantly

that

they

were

very

much

a

family

and

that

race

relations

were

quite

good.

Though

the

media

and

NFL

folk

lore

credits

Gale

Sayers

and

Brian

Piccolo

as

being

the

first

racially

mixed

NFL

teammates,

Verl

Lillywhite

and

Perry

actually

were

the

ground

breakers

and

the

ongoing

example

Perry

set

from

his

entry

to

pro

football

in

1948

until

his

retirement

after

the

’63

season

could

have

served

as a

template

for

others

seeking

the

same

type

of

social

success.

|

On

the

field,

Joe

Perry’s

unselfish

approach

to

the

game

stood

out

as

much

as

his

abilities

to

run

the

ball

for

a

Pro

Football

Hall

Of

Fame

total

of

8378

rush

yards.

Though

he

always

believed

that

his

two

year

AAFC

statistics

and

that

of

the

other

league

players

should

have

been

included

with

his

overall

pro/NFL

accomplishments,

Perry

knew

his

worth

and

was

justly

proud

of

his

body

of

work.

He

understood

that

he

was

a

ground

breaker

as

the

first

NFL

running

back

to

have

consecutive

1000

yard

rushing

seasons

at a

time

when

that

specific

statistic

truly

was

a

fantastic

feat.

He

also

understood

that

it

was

his

job

to

block

like

a

demon

when

sharing

the

“Million

Dollar

Backfield”

with

three

other

Hall

Of

Fame

players

in

John

Henry

Johnson,

Hugh

McElhenny,

and

Y.A.

Tittle

and

that

ball

carrying

chores

would

not

fall

just

to

him.

In

typical

fashion,

he

did

his

job

as

well

as

it

could

be

done.

Still,

from

1949

through

the

’55

season

he

was

the

Niners

leading

rusher

and

the

center

of

the

offensive

attack

that

was

always

one

of

the

league’s

best.