"Eugene Big Daddy Lipscomb"

HELMET REFLECTIONS FOR NOVEMBER 2008

Eugene “Big Daddy”

Lipscomb

By Dr. Ken

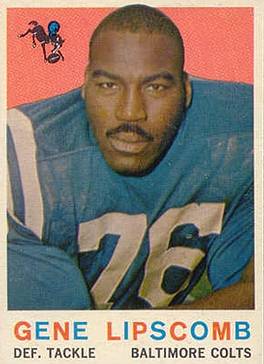

My awareness of

professional football came with an

immediate recognition and

appreciation of a number of players.

Too young to understand the nuances

of the game, I was at least atypical

because my attention was drawn not

to the stars but to lesser known

players. These were the ones with

obvious toughness, those giving

“extra effort,” or what appeared to

be their ability to play a role

larger than that predicted by their

physical size. One player whom I

noticed as soon as I had the chance

to see him on television because of

his size was Eugene “Big Daddy”

Lipscomb of the Baltimore Colts. At

6’6” and 285 pounds, the announcers

were always immediate in following

any play he was involved in with the

comment, “Big Daddy is extremely

fast for his size” and he was

outsized for his era. As a ten or

eleven year old I liked the fact

that he always extended a hand,

albeit one the size of my

grandmother’s cast iron skillet, to

help the ballcarrier he had just

tackled, off of the ground. He was a

monster that was always recognizable

on the field and his 1959 Topps

football trading card became a

favorite in my collection.

|

As a youngster that was brought up in Brooklyn and Point Lookout in the New York/Long Island area, I was predictably, a Giants fan but there were some teams I had a fondness for primarily because they were usually terrible. A sucker for the underdog, I was actually thrilled when Lipscomb was traded to the downtrodden Steelers for the 1961 season, an organization known for beating the stuffings out of opponents but rarely winning meaningful games. In Pop Warner League football games I tried to emulate the smallish fullback Tom “The Bomb” Tracy, thought Bobby Layne was the toughest quarterback in the game, and was quick to see that Ernie Stautner, despite the Steelers losing records, was an absolutely great player. As a voracious reader I had gone through the November 12, 1960 Saturday Evening Post magazine article about Lipscomb numerous times. I loved to read but kept coming back to this specific article because I couldn’t believe that someone as fierce and large as Lipscomb, muscular and seemingly devoid of body fat unlike most of the gridders of similar size, would be afraid of anything. Yet, the title of that article, “I’m Still Scared,” spoke volumes about the emotional scars he carried. As an eleven year old living in a Detroit rooming house with his mother he watched her leave for work and was informed shortly after her departure that a male acquaintance had stabbed her forty-seven times at the bus stop. Raised from that point on by his maternal grandfather, he described what surely was a great deal of physical abuse. He wrote that his grandfather “did the best he knew how. But for some reason it was always hard for us to talk together. Instead of telling me what I was doing wrong and how to correct it, my grandfather would holler and whip me.” Gene was a star football player at Miller High School and held a number of “adult type” of jobs while attending high school, including a graveyard shift at a steel mill prior to going to his high school classes. Suspended from high school sports after his junior season for accepting payment to participate in a summer baseball league, Lipscomb dropped out of school, worked full time, and ran with a crowd of older “hustlers” who introduced him to alcohol, pool, and the temptations of the street. Married to a twenty-five year old woman when he was eighteen, the union ended in divorce and he joined the Marines. Gene played a highly respected level of football and played it well at Camp Pendleton, well enough for the Rams to sign him upon his discharge and actually play him after joining the team with two games left in the 1953 season. Relatively inexperienced, rough, and without technique, he was invited to camp for 1954 and made the squad but for the next few years, was dependent upon his size, speed, and strength to survive on the field. He earned the nickname “Fifteen Yard Daddy” for all of the penalties he incurred for unnecessary roughness, believing that if he could physically beat his man down, his lack of technique would not be a factor.

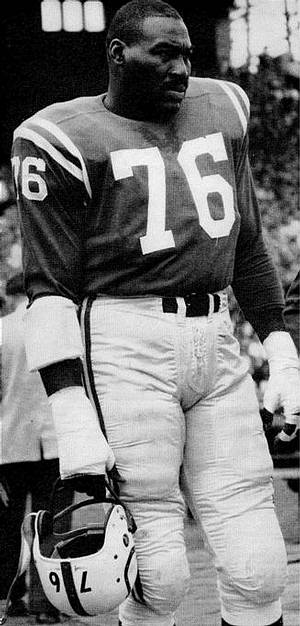

Traded to the improving Colts in 1956, Big Daddy quickly learned technique from a few players who can be considered the best in the pro game’s long history. Hall Of Famers Gino Marchetti and Art Donovan took Lipscomb under their wing and he developed into an All Pro performer. It was noted by a number of the Colts that though listed at 265 to 285 pounds, Big Daddy’s true weight was actually closer to 320 pounds and he never looked sloppy or out of condition. Yet, Lipscomb’s many lifelong insecurities remained and it was obvious to those around him that he was extremely troubled by the emotional abuse caused by his outstanding size relative to others, his lack of education and poor academic skills, the horrific death of his mother, and the indignities cast upon him as an African-American as was typical for that era. His Rams teammates had left scars as they had continually chided him for his “stupidity,” absence of any collegiate experience, and penchant for drawing penalties. Lipscomb at times referred to his attendance

|

at “Miller Tech,” citing his former high school, to perhaps give the impression he had attended college for a time. Even his nickname “Big Daddy” was attributed to his inability to remember the name of some of his teammates and he would instead refer to them as “Little Daddy” thus leading to his name of “Big Daddy.” The public was not aware that two subsequent marriages were unsuccessful and Lipscomb yearned for the family life he never had, thus leading to bouts of alcohol abuse. Even as an All Pro performer, he was afraid of having his job taken. With the Steelers, his arrival coincided with a reprise of solid team play and after his two seasons there, he had garnered All Pro honors a total of four times in his career. He was popular as a professional wrestler in football’s off-season and this provided a way to earn additional income. Despite the recognition and success, Lipscomb could not escape the effects of his childhood experiences or what seemed to be perpetual marital discord and divorce related difficulties. It was rumored that his friends were still the “hustler types” and street hoodlums he had grown up with, thus perhaps it was inevitable that Big Daddy would meet a sad and violent end.

Former NFL and AFL defensive back Johnny Sample was best friends with Lipscomb and noted in his autobiography that he had spent every waking moment the weekend prior to Big Daddy’s death with him and at no time, then or in the six years they had been close, had the use of narcotics ever been discussed relative to Lipscomb. Although Big Daddy drank excessively, often two-fifths of VO Whiskey per day as a usual ration, no one had ever seen him use any type of drug. Yet on May 10, 1963 his body was found on the sidewalk in front of a Baltimore hospital with three fresh needle punctures in his right arm. As

|

Sample noted, as a right-handed individual, it would make no sense for Lipscomb to have injected himself in his right arm, thus the injections were administered by another person. Big Daddy had been on the town drinking with two women and some men he normally did not associate with and had been carrying a large amount of money he had just received after completing a radio commercial. Those close to Lipscomb cited his fear of needles and despite the medical examiner’s ruling that death came from on overdose of heroin, insisted he was not a drug user. Evidence on the body indicated that attempts to revive the big lineman had been made and many believe that being already drunk, Lipscomb was injected with heroin as part of a robbery scheme and the death was accidental.

To this day, the

tragic end of Eugene Lipscomb

remains a mystery to many and has

tarnished his legacy. Often called

one of the greatest defensive

tackles of his ten year era, his

name is rarely mentioned when

outstanding players are discussed or

considered for posthumous honors. He

was one of he first of the very fast

and quick men who were also bigger

and stronger than almost every

opponent, the prototype for the

modern defensive lineman. His

arrival in both Baltimore and

Pittsburgh was coincidental to

significant improvement in the play

of each defense yet he remains

unappreciated and forgotten. The

death of Big Daddy Lipscomb will

remain a mystery and a black mark on

the game but for those of us who saw

him play, he was truly a force to

contend with.