"GEORGE ANDRIE"

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS September 2018:

"GEORGE

ANDRIE"

By Dr. Ken

For

our

HELMET HUT

readers and

fans who can

recall

watching

football

from the

1950s

through the

early to

mid-1970s,

it is sad to

note how

many of

those

players have

passed away

recently.

Every year,

every month,

and every

week seems

to bring

another

well-known

name from

the past to

the obituary

page.

Although the

statistics

vary

relative to

whom is

“making

their case”

or proving

their

argument,

collegiate

and

professional

football

players

either die

at a

relatively

younger age

than their

non-participating

peers or

close to the

average age

of passing.

We are

reminded of

the old

adage from

Mark Twain

that

“Figures

don’t lie,

but liars

figure.”

What we do

know is that

it is now

epidemic, if

only due to

“old age”

that our

former

heroes are

leaving us

as they

enter their

seventies,

eighties,

and

nineties. We

all have

specific

memories

that have

made the

game of

football

meaningful

thus some

deaths are

more

important to

us than

others.

Certainly

the

HELMET HUT

staff at one

time

discussed

presenting

articles on

the better

known or

successful

players who

were

recently

deceased

before it

immediately

became

obvious that

one could

not truly

keep up with

the mounting

count nor do

service to

these

excellent

athletes.

On August

21, 2018

former

Dallas

Cowboys

defensive

end George

Andrie died

from

congestive

heart

failure

although his

battle with

CTE was well

known among

the NFL

“concussion

lawsuits.”

Andrie was

one of those

players who

caught my

attention

early in his

professional

career, in

part due to

his

collegiate

background

that was a

bit unusual.

I had

personal and

“up-close”

knowledge of

the

elimination

of football

at a major

university

and as

literally

traumatic as

this type of

event can be

for current

students and

alumni, it

is tragic

for players

and coaches.

Hofstra

College was

founded in

1937 as a

Long Island

extension of

Manhattan’s

prestigious

New York

University

and was

established

as an

independent

college in

1939. It

primarily

served as a

commuter

school for

Long Island

students but

was diligent

in building

an excellent

academic

reputation

into the

mid-1960s.

It was

granted

university

status in

1963 and

embarked on

an expansion

program that

included the

construction

of numerous

on-campus

dormitories.

Like many

private

universities

that faced

financial

challenges

during a

time of

student

protest,

Hofstra’s

very public

“campus

takeovers”

dictated a

lowering of

academic

standards in

order to

remain

financially

solvent.

This of

course was

vehemently

denied by

the school

administration

but even

some of the

Ivy League

bastions

were forced

to do the

same as

parents were

hesitant to

send their

children to

what were

deemed

unsafe

centers of

student and

social

strife. What

had once

been

considered

“just a

notch below

Ivy League

status” for

Hofstra,

leveled off

to “just

another

college” in

order to

maintain a

student

enrollment

that was

usually in

the 10,000

to 12,000

range.

Whatever

question

Hofstra’s

final head

football

coach Dave

Cohen is

asking an

official

could have

been asked

of the

school

administration

when they

dropped the

program

without

notice in

2009

Hofstra’s

Flying

Dutchmen

began to

play

football

when it was

first

granted

independence

from NYU in

1939 and

playing at a

variety of

small school

levels, they

played well,

competitively,

and

occasionally

attracted

national

attention

and

developed

professional

level

players.

Their

stadium and

training

facilities

were on par

with the

upper tier

Division

III, II, and

eventually

Division 1AA

which was

their final

stop. One of

the young

men who

lifted

weights in

the author’s

garage was

David Cohen,

an excellent

though

undersized

defensive

tackle at

Long

Island’s C.W.

Post

College, a

long-time

rival of

Hofstra when

they played

at similar

levels. Dave

followed his

collegiate

career with

a number of

assistant

coaching

stops on the

East Coast,

earning many

accolades as

a defensive

coordinator

and

recruiter.

He became

Hofstra’s

head

football

coach in

December of

2005 and was

doing a fine

job

rebuilding

the program

when he was

called to a

meeting with

the school

President

and Athletic

Director on

December 3,

2009.

Believing he

was notified

in order to

finalize a

promised

contract

extension,

he was

instead

informed

that the

university

was

terminating

the football

program due

to financial

considerations.

Northeastern

University

had made a

similar

announcement

only weeks

before. I

watched Dave

and his

dedicated

staff do

everything

possible to

assist

players,

both

scholarship

and

walk-ons, to

find other

viable

alternatives,

making phone

calls late

into the

night,

meeting with

parents and

players, and

doing what

could be

done to

insure that

their

educations

were

protected.

Those

players at

Hofstra on

scholarship

were allowed

to complete

their

degrees with

all expenses

paid.

However,

trying to

salvage

dreams,

finances,

academic

continuity,

and

restarting a

college

football

career

elsewhere

literally

from

“square-one”

was

overwhelming

for many

players. The

coaches did

the same

while

protecting

their

players as

much as

possible and

then

uprooting

their

families.

For many

like Dave

Cohen who

went on to

build award

winning

defenses at

a number of

schools and

who is

currently

the Run Game

Defensive

Coordinator

at Wake

Forest,

things

worked out

but the

process is a

nightmare.

George

Andrie’s

collegiate

career ended

in similar

fashion.

George was a

tall, slim

two-way end

at Catholic

Central High

School in

Grand

Rapids,

Michigan,

also

starring in

basketball

and

baseball. He

was All

League, All

City, and

All State on

the gridiron

and

entertained

athletic

scholarships

from a

number of

schools

including

Michigan

State. With

that local

powerhouse

knocking,

the Spartans

would have

been a

logical and

understandable

choice but

George’s

older

brother Stan

had been a

stand-out at

Marquette

University

and as

George

humorously

but

accurately

stated in an

interview

years later,

“I was a

good

Catholic boy

and my

mother

wanted me to

go to a good

Catholic

university

so I chose

Marquette.”

The

Milwaukee

based school

boasted high

academic

standing, a

tradition of

basketball,

and a

Warriors

football

team that

generally

remained

competitive

with its

national

base of

other

Catholic

institutions.

Although the

mid-to late

1950s were a

down time on

the

gridiron,

the 1959

team boasted

a number of

good players

who later

had pro

careers in

Andrie, Karl

Kassulke,

Pete Hall,

and John

Sisk, Jr.

1959’s star

running back

Frank

Mestnik was

a first

round draft

choice of

the 1960

Boston

Patriots and

won the

starting

fullback

position

after

signing with

the St.

Louis

Cardinals.

Attendance

had risen,

the team’s

prospects

for 1961

looked

promising

relative to

‘60’s 3 – 6

record, and

campus

enthusiasm

was high as

the campaign

concluded.

The December

9, 1960

announcement

that

terminated

the football

and track

and field

programs

came as a

shock, even

though in

the

twenty-five

preceding

years,

twenty

Catholic

college

football

programs had

been

shuttered.

These ranged

from

Portland and

Niagra

Universities

to

nationally

ranked

Fordham and

the

undefeated

1951

University

of San

Francisco

program that

had featured

Hall of Fame

members Gino

Marchetti,

Ollie

Matson, and

Bob St.

Clair, as

well as Dick

Stanfil who

had

graduated

the year

before. Long

time pro Ed

Brown

quarterbacked

the team

that also

placed Joe

Scudero and

Red Stephens

into the

NFL. Burl

Toler was

injured in a

post season

all star

game after

being

drafted by

the

Cleveland

Browns which

led to his

outstanding

officiating

career.

When

Marquette

ended their

program,

Andrie, as

an excellent

athletic

pass

receiving

tight end

and

defensive

end, had a

number of

offers to

consider for

his senior

football

season and

academic

work. At

6’6” he was

considered

the tallest

back in the

country as

he would

often move

to a

slotback

position on

offense. He

visited

Tulsa,

decided to

stay and was

doing well

on the field

but noted

that “three

weeks into

the semester

he still had

not been

assigned to

any

classes.”

Being

serious

about

attaining

his degree

and having

met a young

woman on the

Marquette

campus who

had garnered

his

affections,

one who

became his

future wife

of course,

he hurried

back to

Milwaukee to

accept an

offer to

have his

tuition paid

but without

the

room-and-board,

books, and

other

benefits of

his former

athletic

scholarship.

He spent

what would

have been

his senior

football

season as a

full-time

student,

focused

exclusively

on his

academic

work and

playing

intramural

basketball.

He did not

however

remain

completely

under the

NFL radar as

Gil Brandt,

working as

player

personel

director for

the infant

Dallas

Cowboys

visited

Andrie and

told him

that at 230

pounds, his

6’6” frame

needed more

muscle

tissue. With

Brandt’s

encouragement

and the

$500.00 the

Cowboys gave

him, George

joined what

was then

referred to

as a “health

spa”, signed

with the

Cowboys as a

sixth round

draft pick

and reported

at a solid

245 pounds

which would

increase to

a robust 250

- 260 within

another

year.

Andrie’s

primary goal

was to “find

out how good

I was since

I had not

reached my

full

potential at

Marquette.”

All of

George’s

teammates

immediately

noticed a

work ethic

and

willingness

to put in

whatever

extra time

was needed

to overcome

his lost

season at

Marquette.

The great

Bob Lilly

who played

next to

Andrie on

the Doomsday

Defense line

said of

George, “He

had a great

attitude and

was very

intense when

he put his

uniform on.”

He further

stated that

Coach Tom

Landry was

teaching and

installing

his Flex

Defense when

Andrie

arrived and

while “no

one could

learn the

entire

defense in

one year,

George

learned more

than the

rest of us.”

He also

rewarded

Brandt’s

confidence

in him by

being named

to the NFL

All Rookie

Team for

1962.

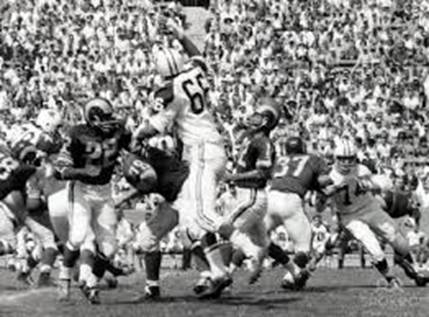

There is

nothing that

could take

anything

away from

the

greatness

that was Bob

Lilly’s

professional

(or college)

football

career but

some experts

have noted

that having

Andrie at

defensive

end next to

Lilly’s

tackle

position

certainly

added to

Bob’s

opportunities

and ability

to make big

plays.

Andrie’s

career,

despite

playing in

five Pro

Bowls,

earning the

1969 Pro

Bowl Co-MVP

Award, being

named First

Team All Pro

in 1964, and

having three

Second Team

All Pro

nominations

was in many

ways

overshadowed

by the

overall play

of Landry’s

excellent

defenses as

well as

Lilly,

middle

linebacker

Leroy

Jordan, and

a number of

Hall Of Fame

defensive

backs.

George

however

would never

be one to

complain

about having

or lacking

individual

awards as he

was a team

player in

every sense

of the term.

Brandt later

said,

“George’s

career was

way above

expectations.

Any time

you’re

drafted in

the fifth or

sixth round

and didn’t

play

football in

the previous

year and did

what he did,

that really

speaks for

itself.”

George

however,

played

because he

wanted to

test his

abilities

against the

best the NFL

had to

offer, see

how good he

could be

relative to

his own

expectations,

and take

advantage of

the

opportunities

the game

offered him

both on the

field and in

later

business

ventures. He

proved his

ability and

his

toughness,

the latter

noted by

teammate

Lilly when

he said,

“George was

a stalwart,

he never

missed

games, he

played with

bad elbows,

bad knees,

cuts,

bruises, all

the things

that in

today’s

world guys

wouldn’t

play with.”

He always

went all out

and his

teammates

looked to

him when a

great

performance

was needed.

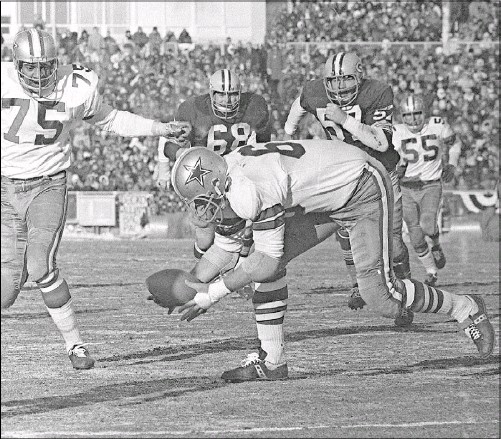

Cowboys

guard John

Niland

related that

“You could

count on

him,

especially

in the big

games. He

always had

his head in

the big game

and always

played very

well.” One

of the

enduring

memories of

that

statement

came in the

1967 NFL

Championship

“Ice Bowl”

Game with

George

scoring a

needed

first

Cowboys

touchdown

after

pursuing

Packers

quarterback

Bart Starr

for a loss,

fumble, and

fumble-recovery

seven yard

touchdown

run to kick

start his

team in the

second

quarter.