"OFF - SEASON TRAINING AND PRACTICE, HIGHLIGHT TIME FOR US LESSER LIGHTS!"

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS August 2018:

"OFF

- SEASON TRAINING AND PRACTICE,

HIGHLIGHT TIME FOR US LESSER

LIGHTS!"

By Dr. Ken

For football players that lack the talent or skills possessed by many of their teammates, the summer off-season training period and official football camp hold as much importance as the actual in-season games played before tens of thousands of fans. When one is determined to improve as much as possible and in turn help his team play as well as possible, this then becomes an acceptable and understandable statement. Admittedly at any level, I was never as “good” as most of my teammates and knew it but made that a positive point by utilizing any obvious comparative shortfalls as a means of motivating myself to do more than others or better than others. “The Others” was in fact a term used by late 1960s hippie linebacker Ralph “Chip” Oliver of the Oakland Raiders to identify the non-starting, “lesser” members of the team, described in newspaper articles as not the all-stars, not “heroes,” but “the other guys” as per

“the Raiders starters played great …with help from the others…” .

These were back-ups and special teams players with limited roles, motivated by their esprit-de-corps that pushed them to play harder. I was probably typical of a middle-of-the-pack participant who had to do more work and harder work just to keep up. I was truly a member of “The Others.”

In an era when the term “jogging” had not been introduced until 1963 by famed Oregon track coach Bill Bowerman, I was already a regular off-season runner by the age of eleven. I was routinely stopped by our local police officers as I did what my father and his boxing and racetrack buddies referred to as “road work.” Even at that relatively young age I already understood that as one of the smallest children in my grade, I needed “something” to allow me to compete and jogging or running slowly for many miles was part of the answer. With public running or jogging not yet a burgeoning fitness activity, law enforcement had but one frame of reference for a rapidly moving individual of any age on the street and I was frequently chased off of the Long Beach roads for “running from someone” or “fleeing a potential crime scene.” I found that running on the beach or in knee deep water at the edge of the surf, even at 2 AM as a high school student with study and work responsibilities, obviated the problem with the police and actually allowed for a higher level of conditioning than running at the school track or in the streets. I was an early advocate of weight training, taking a truck axle, flywheels, and gears from abandoned vehicles that had been dumped in the empty lot next to our house and fashioning make-shift barbells from the pile of scrap iron. Partially filled pails of concrete or cement completed an effective backyard gym and from the age of twelve, the end of May which also marked the end of high school track season also began my “football season.”

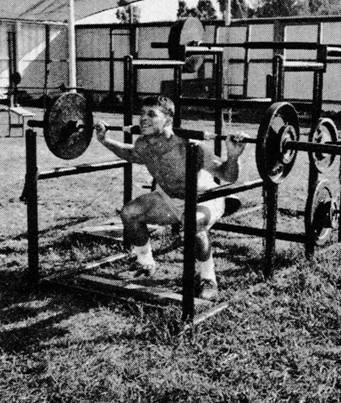

Chargers fullback Keith Lincoln performing barbell squats at 1963 training camp. Sid Gillman brought in Alvin Roy as a part-time “strength training consultant” and credited his work as a key factor in the team’s AFL championship season

There were like-minded players in our area, often from other schools and with the beach as a magnet for teenagers and college aged athletes we often found each other. I was fortunate to be accepted by older players and allowed to run and perform drills with them. The “walk-throughs” of specific plays and “touch football” games in the sand frequently deteriorated into harsh full contact drills and an occasional fist fight which also proved to be terrific training for what was to come. The start of official practice was unlike the handkerchief dropping sessions that are now standard procedure. I am an advocate for player safety and having been hospitalized eleven times for definitely diagnosed concussions, I certainly understand the ramifications of traumatic head and brain injury. However the game of that era was much more physical in its play and much more physically demanding with many players still going both ways and always available, even at the college level, to participate as an offensive or defensive player. One had to be physically and mentally conditioned to meet those conditions and thus all practices were carried forth in full uniform and were much more physical in nature, with full contact of some sort and first team-against-first team scrimmages during game weeks de rigueur. Thus everyone’s preparation was more demanding with the southern and southwestern teams most frequently mentioned when hard, tough training camps were discussed. Bear Bryant, Darrell Royal, Charlie Bradshaw, and Jim Owens were usually noted as requiring exceptional physical preparation before entering camp and as nationally known programs at Alabama, Texas, Kentucky, and Washington, this would have been expected. However, many of our group besides playing at the usual top choices in our area of Ohio State, Penn State, Notre Dame, Purdue, and Maryland, also had representation at smaller schools. Wooster, Oberlin, and Denison in Ohio, Guilford and Frostburg State “down south,” and local Hofstra and C.W. Post all rostered locals and most provided them with some sort of pre-season handout for running and drill recommendations, often of a challenging level.

First team offense vs first team defense scrimmages in camp and throughout the season were standard into the 1970s. Note overalls-type of padding worn to protect some of the linemen in photograph from 1962 Green Bay Packers camp

Even at Division 3 colleges and universities where football participation is most frequently voluntary and not tied to monetary supplementation, participants are engaged in supervised all-year training. At the D1 and D2 levels players can expect to be on campus almost twelve months per year, enrolled in summer and winter semester classes so that they can participate in off-season team strength training and football specific activities. No one is “left on their own” to prepare for spring football or an upcoming season, even as a dedicated group. All aspects of the preparation program are monitored. Players remain on campus, ensconced in air conditioned dormitories, sitting in air conditioned classrooms, and usually prevented from finding jobs that engage them in construction, road maintenance, iron working, farming, logging, or other forms of manual labor. They are expected to be in condition from the organized physical activities provided by the coaching staff. For many players, their saving grace is the high level of specialization the game now reflects with most players participating in a limited number of plays each game or in a consecutive manner. Thus the overall level of conditioning for almost all of them does not have to be that high and for many, surprisingly, it’s not.

Padded helmets and knee braces for all are a positive step in fall practice drills but the only way to become conditioned for full contact game-speed collisions in full uniform is to practice in that manner often enough to become conditioned to it

A high level of conditioning brought by the college players of the 1950s and ‘60s often reflected the military backgrounds of their coaches and a number of the players themselves. Numerous colleges had three-a-day practices for the first week of what was usually a six to ten week pre-season practice period. No matter what the NCAA rule might have been, players were often at a camp site off of campus or settled into a dormitory by the final week of July or first week of August with opening games in mid to late-September. Early morning and late afternoon or evening practices lasting approximately ninety minutes to two hours were designed to coincide with a “cooler” part of the oppressive summer days but a third shorter practice would be held in the mid-day heat. This was often no more than an hour’s worth of full contact drills designed to eliminate those players deemed to have less than a full commitment to a team goal of indefatigable effort and play.

Pre-season practice in the late 1950s where a lot of contact during every practice session was expected

Unlike today’s collegiate player whom rarely leaves the campus, one was expected to return home for the summer months, pursue a manual labor based job, run before or after work, find time to do position or team calisthenics and team type drills with like-minded friends or former high school teammates, and for the very few who lifted weights, somehow work that in to the schedule also. Having suffered many on-field concussions and admittedly a number off of the field, the author concurs with steps that obviate that possibility. However, the relative absence of contact work among college and especially professional football players during their preparation period remains “the elephant in the room” when discussions of “why” there are so many football related injuries. A standard discussion some of our group of aspiring and often successful college football players had always led to the conclusion that we could spend the summer months in jobs requiring demanding manual labor, lift weights to enhance strength, run on the beach, through sand dunes, and in knee-deep water resulting in tremendous levels of cardiovascular and local muscular endurance, and still suffer with exceptional muscle soreness and body fatigue once actual contact began. Once the hitting was initiated in football camp, we would all have significant soreness and feel as if we had done little to prepare ourselves. “The only way to prepare for being hit is to be hit” was always our conclusion and our coaches concurred. If the modern football player has very minimal contact in preparation for the brutal contact of the game, how would there not be an increase in the frequency and severity of injury?

At 6’3” and 245 pounds, Dick Butkus was large enough to be one of the best of all time, college or pro

Many point to the size, both height and weight, of players at all levels of football relative to those of the 1960s. Three hundred pound players were a rarity into the late 1960s because of the demands of going both ways even at the collegiate level, the running and conditioning requirements necessary to prepare for a game that was unlike the glorified basketball-on-grass or enhanced-seven-on-seven passing games that are now standard fare. The level of obesity among active college and professional players is undeniable and worse for the majority after they leave the game. This is a result of the diminished necessity for high levels of conditioning. The specialization that brings many players to the field for no more than fifteen plays per game differs markedly from the readiness level of being prepared to play two or three times that number. For those of us who were much less than team stars, gridiron heroes, or stand-outs with bulky notebooks of newspaper clippings, always being in excellent physical condition, being physically able to go all out during every drill or play in practice, and having the capability to bring out the best in our teammates were the driving force that maintained that high level of fitness and made the game enjoyable. In the opinion of many, it made the game much better!