BOWLING FOR THE RIGHT REASON

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS December 2016:

BOWLING FOR THE RIGHT REASON

Part Two of CINCINNATI’S TAFT

HIGH SCHOOL BACKFIELD which will

continue the Part One feature of

November 2016, will be published

as the Helmet News/Reflections

column of January 2017

By Dr. Ken

The 2016 NCAA Football

Bowl Subdivision,

previously known as

Division 1 Football,

will end with forty bowl

games excluding the two

semi-final and

concluding championship

contests. The NCAA

Football Championship

Subdivision, the

previous D-1AA, has its

own championship playoff

schedule and an all-star

game but it is almost

mind-numbing that there

would be forty

post-season bowl

match-ups. These games

include the traditional

Rose Bowl and Orange

Bowl games as well as

the recently minted

Bahamas Bowl, Cure Bowl,

and Arizona Bowl games.

The proposed slate for

the near future includes

games in Dubai,

Australia, and Ireland.

Purists don’t like it

and those who love the

game of football for its

fundamental aspects

don’t usually like the

glut of bowls either. We

are saddled with

mediocre teams that may

have failed to manage a

break-even season, often

with players less than

fully motivated to play

in a third-tier bowl

game that requires

additional weeks of

post-season practice

during time that would

otherwise be spent

healing previous

injuries and contusions

and catching up with

their academic and

social activities. For

the same reasons that

players often dislike

participating in bowl

games, football coaches

love it.

Once the season is over

for a team that is not

bowl-bound, it is over

until spring practice

begins. Of course there

will be winter workouts,

supervised strength

training and running

activities but actual

football workouts are

prohibited unless... The

“unless” is

participation in a

sanctioned bowl game.

This allows coaches

three to six weeks of

legal, additional, “just

like if we were in the

middle of the season”

practice. It allows

blocking, tackling,

drills, film sessions,

and everything else that

goes into making a

football program

successful and every

bowl participating team

has this additional

“work time” advantage

that those that are not

bowl invited, will not

have prior to going into

spring ball or fall

camp. Thus, is it any

wonder that coaches love

bowl games? Let’s be

very upfront in our bowl

related conversation.

Not one of the forty

bowl games to be played

in this year’s

post-season period has

been arranged in order

to lose money. With

payouts to each team,

advertising, gift bags

to coaches, players, and

staff members, meals,

banquets, organized

tours of local

attractions, travel

related expenses, staff

salaries, stadium

rentals, and numerous

other associated

expenses, there

obviously exists an

opportunity to make a

profit and the belief

that one can in fact be

made. Even if the profit

is not realized in

quantified dollars, the

exposure for the host

city, the money made in

tourism at the time of

the game or from future

visits, and the national

and repetitive mention

of sponsors all bring in

revenue at some point in

time. The television

exposure and mention of

the participating

universities’ names

prior to, during, and

after the game is often

“the kind of advertising

you just can’t pay

enough for” and one can

add the recruiting

prestige of having

played in a recent bowl

game. Thus, one might

ask, “How can they have

forty bowl games?” but

happily, somewhere along

the bowl contest

journey, everyone seems

to benefit.

Many bowl games “attach

themselves” to a local

charity. This enhances

the “acceptability” of

the game and the bowl

committee, legitimizes

and attracts attention

to the game and its

broadcast. The public is

more inclined to look

favorably on a bowl game

that features the

participating athletes

visiting local hospitals

or other needy projects

as opposed to one that

lacks this sentimental

note. This is not to

state or imply that the

bowl games affiliated

with a specific charity

or cause are in any way

disingenuous but as

today’s media relations

experts would say, “it

provides a better

optic.” On a personal

note and as an obvious

example, I always looked

forward to the

television broadcast of

The East – West Shrine

Game, the annual

all-star game played

each January following

the various bowl and

college playoff

contests. This is a long

established game that

has been sponsored by

the fraternal group,

Nobles of the Mystic

Shrine, better known as

“The Shriners,” and the

funds that come from

this game go to a number

of their projects, most

obviously the Shriners

Hospitals for Children.

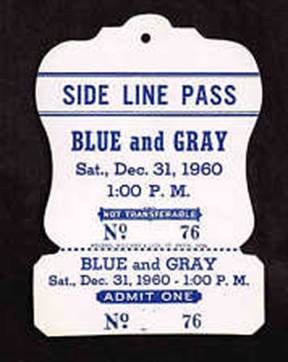

During the 1960s when my

interest was greatest,

the East – West Shrine

Game always seemed to

have a few of the

biggest names in college

football while the Blue

– Gray Classic, played

on Christmas Day, had to

“settle” for players

whose teams did not

qualify for any bowl

contests. Even when

there were but four

major bowls and few

others such as the Sun

Bowl, the Blue – Gray

Classic had more

relatively unknown

players or those from

smaller colleges. This

factor made it a very

interesting game to me

as unlike much of the

public, my obsessive

reading and study of

college football,

especially during my own

years of participation,

forearmed me with some

knowledge of each player

prior to the game’s

start. The Blue – Gray

Classic also featured

many players from the

“deep south” schools

which from the late ‘50s

through early 1970s

meant fast, hard-hitting

football, even weeks

after the end of the

regular season. This

game too was affiliated

with charitable works

and always exciting.

One of the best bowl

games was held on

Thanksgiving Day of 1961

with “one of the best”

defined as “being done

for all of the right

reasons.” Before delving

into the specifics of

this bowl game however,

it is necessary to

mention the tragedy of

October 29, 1960. The

football game between

California Polytechnic

State University located

in San Luis Obispo,

California and host team

Bowling Green State

University in Ohio had

been a 50 – 6 romp for

the home team. Although

Cal Poly had played well

for their head coach

LeRoy Hughes, winning

approximately two-thirds

of their games every

season since his 1950

arrival, the Bowling

Green game left the

Mustangs at 1-5 for the

’60 season. The trip

east for the Cal Poly

team was in itself a bit

of a departure from its

usual games against

other California state

supported universities,

most members of the

California Collegiate

Athletic Association.

The C-46 military

transport plane used for

the trip by Arctic –

Pacific Charter was

described as “a relic

from World War II” and

put in a busy day. The

round trip between

California and Toledo

was augmented by a

flight to Connecticut

where the airplane

transported the

Youngstown University

team home from its game

against UConn. With a

few hours of waiting

time to deal with, many

of the Cal Poly players

attended Halloween

parties on the Bowling

Green campus or sat and

became acquainted with

their Bowling Green

Falcons opponents. When

it was time to depart,

there were further

delays due to the dreary

weather and dense fog

that fell upon the area.