JIM SWINK, UNDERSTATED HERO

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS October 2016:

JIM SWINK, UNDERSTATED HERO

By Dr. Ken

On the eve of the start of

the Presidential Candidate

Debates of 2016, current

events that have highlighted

the cultural, political, and

social turmoil of our times

have no doubt stimulated

wistful thoughts of a

simpler and more genteel era

for those who enjoyed their

adolescence during the 1950s

and ‘60s. My teen years came

in the late ‘50s to

mid-1960s and few would call

the last half of the Sixties

“simpler and more genteel”

as anti-war protests, civil

rights unrest, and social,

political, and cultural

upheaval highlighted what

seemed to be every day’s

news. Yet the “psychological

environment” produced by the

game of football seemed to

have a calming if not

stabilizing effect on much

of the nation, in part

reflecting the relative

innocence of the1950s. By

the end of the Sixties,

football itself would be a

bit of a battleground with

some college campuses

hosting heated debates about

the sport’s perceived

brutality, relevance,

war-like analogies, and

“dehumanization.” Without

meaning to sound

insensitive, and expressing

opinions that are solely

those of this author and not

necessarily reflective of

HELMET HUT

or other staff members,

recalling and re-reading

numerous accounts of college

campus and football related

protests and their

underlying reasoning and

specific complaints make one

think, or at least make me

think, “What a waste!” To

know that careers were

ruined and choices were made

to forfeit scholarship money

and the loss of being able

to play a game every

involved athlete no doubt

loved because they believed

that their “personal freedom

was violated” when asked to

insure that their hair did

not protrude beyond the

bottom of their helmet, or

that their “civil rights

were violated and cultural

traditions disrespected”

because the team rule

forbade facial hair seems

short-sighted from the

perspective of one of my

age. I can recall that even

in the late 1960s, feeling

as if there were many

aspects of athletics and

“just life” that were

forever altered from the

dominant tenure of the

previous decade.

If ever a reminder of “all

that was right” about 1950s

football was needed, Jim

Swink is the embodiment of

that construct. He grew up

in Sacul, Texas, the son of

a logger and his wife who

both fell to illness when

Jim was thirteen years of

age. He moved in with a

couple in the nearby East

Texas town of Rusk where his

athletic abilities became

apparent. He was an All

State football player and

All District in both

football and basketball. He

was chosen for the Texas

High School All-Star

Basketball Team his senior

year and was named the

game's Most Valuable Player.

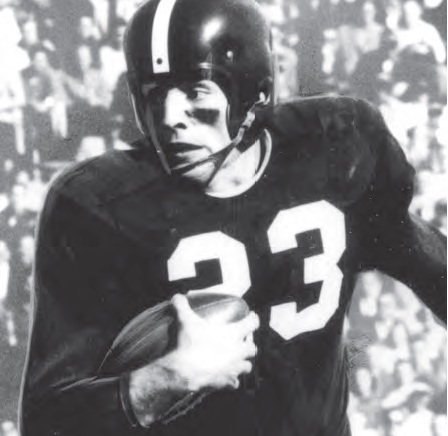

Swink vs Jim Brown in

the January 1, 1957

Cotton Bowl. It isn’t

often that two great

College Football Hall of

Fame members get to face

off

He entered Texas Christian

University in part because

of a relationship he

developed with head football

coach Abe Martin, a folksy,

country gentleman with whom

Swink felt very comfortable.

The lean 6’1”, 185 pound

back had obvious speed but

ran with deceptive power

that was obvious in his 1954

sophomore season when TCU

made the decision to play a

sophomore laden team and

finished at 4-6. Martin

parlayed the experience

gained by those youngsters

into a 9-1 regular season

finish in 1955, a close and

heartbreaking 14-13 loss to

Mississippi in the Cotton

Bowl, and a number five

end-of-season ranking. There

were a number of excellent

players on the squad

including future New York

Giants back-up quarterback

and Texas high school

coaching great Charles

“Chuck” Curtis but it was

Swink that was the team’s

engine. On but 157 carries

the “Rusk Rambler” rushed

for 1,283 yards, an

impressive 8.2 yards per

carry, and scored twenty

touchdowns while

contributing to the Frogs

overall total offense that

was ranked second in the

nation. He was a Consensus

All American and second in

the Heisman Trophy voting to

Ohio State’s Howard Cassady.

In a big game against Texas,

Swink ran for 235 yards and

four touchdowns, one of

which became legendary in

Lone Star State football

lore. On his sixty-two yard

jaunt he swept left, cut

right, went back to the

left, stopped short as two

Texas defenders literally

overran him, and completely

befuddled the defense.

Teammate Vernon Uecker

stated, “Don Cooper and I

were supposed to be blocking

but Jim ran by us so many

times we finally just stayed

on the ground and watched

the show.”

1956 was similar to ’55

for both Swink and TCU

as the All American led

the Frogs to an 8-3

slate and a hard-fought

28-27 Cotton Bowl win

over Jim Brown and

Syracuse. Despite having

every team key on him,

he still led the

Southwest Conference in

rushing and completed

his college career with

2,618 yards. Described

as “an elusive,

courageous runner with

amazing balance and

timing” Swink elevated

the excitement level for

every fan in the

stadium. His head coach

described him as “…just

a little ol’

rubber-legged outfit

nobody can tackle” and

every opponent saw Swink

as the difference maker

when it was time to play

the Frogs. An eventual

member of the College

Football and Texas

Sports Halls Of Fame,

winner of the

Pricewaterhousecoopers

Doak Walker Legends

Award, and the 1956

recipient of the Swede

Nelson Award for

sportsmanship, Swink was

most proud of being a

NCAA Silver Anniversary

honoree for combined

achievements in

athletics and

professional life, and

his membership into

GTE’s Academic Hall Of

Fame. It was the

emphasis on scholarship

that allowed him to

ignore a professional

football career after

being drafted in the

second round by the

Chicago Bears and

instead begin his

medical school studies.

Swink said “The Bears

drafted me and it was

tempting. George Halas

used to call me up and

talk for an hour. He’d

say ‘I need someone up

here who doesn’t fumble

the ball’ but I just

couldn’t fit it into my

schedule.” While hard to

believe, his schedule of

medical school study

followed by internship

and a residency just did

not leave time for

football. While at

Dallas’ Parkland

Hospital, he signed with

the Dallas Texans

inaugural 1960 American

Football League team but

after five games, made

the decision to focus on

his medical career,

again citing an

inability to make

football a full-time

endeavor. Swink said, “I

just couldn’t do it full

time. I probably would

have played longer if it

were possible.”

He established himself as a

respected surgeon and to

this point perhaps his story

does not differ from many

other outstanding

scholar-athletes. Swink

however, in keeping with the

1950’s dictum of trying to

do “everything the right

way” served a tour in

Vietnam where he was known

as “a hell of a Battalion

Surgeon.” He always

understated his military

service and the medals won,

just as his modesty and

quiet demeanor would rarely

allow him to mention his All

American glory days at TCU

unless it was first brought

up by others. Serving as an

Army medic, he eventually

was in the field with the 1st

Infantry and often ignored

the fighting that raged

around him while treating

the wounded. He described

his service as “just a

matter of trying to make the

best of a bad situation. We

had a few medics, but I was

the only doctor in the

battalion…I made twenty-five

helicopter flights and every

one was bad. I finally got

hit by shrapnel just trying

to dodge bullets.” Dr. Swink

neglected to mention in this

specific interview but as

reported by General Jim

Shelton, a Major at the

time, who witnessed the

battle site, that there was

a bit more to the

explanation. Shelton noted,

“After this battle I was to

learn that he was the same

Jim Swink who was an All

American tailback at Texas

Christian University in the

early ‘50s when I was

playing in college at

Delaware. His picture had

been on the cover of every

football magazine in the

country. He had gone to

medical school after TCU and

was serving his time in the

Army when he was sent to

Vietnam. He had gone

immediately to treat the

wounded that night and had

been shot in the shoulder

himself. He continued to

treat the wounded, although

when I had called to him he

was bleeding from a wound of

his own. He received a

Silver Star for his cool

actions that night, working

with the wounded though

wounded himself.”

James Swink, reluctant

combat hero but a true

hero

When his Army commitment

was completed, Swink

returned from Vietnam as

a Captain, receiving the

Purple Heart, Bronze

Star, Silver Star, Air

Medal, the Combat Medic

Badge, the Army

Commendation, and the

Vietnamese Crown of

Gallantry. He entered

civilian life and

practiced orthopedics in

Fort Worth. He returned

to Rusk, Texas and in

2006, again had the

opportunity to display

his uncommon courage,

humility, and devotion

to service after

suffering a stroke, yet

continuing to treat his

patients. James Perkins,

a lifelong friend and

Rusk High School

teammate summed Swink up

well, “Jim Swink is an

American hero and a role

model for our entire

country, he’s proof that

in America, the

opportunities are

unlimited if you are

willing to work. His

ability to continue

working with the serious

disabling handicaps is

as much an inspiration

as his All-American

athletic

accomplishments, Purple

Heart and distinguished

medical career.” When

he passed away on

December 3, 2014,

Swink’s wife stated the

obvious and repeated

what everyone said about

her husband, “He was a

darn good man.” Jim

Swink was all that we no

longer see often enough

within the fabric of

life and athletics in

our nation. He didn’t

believe that anything he

accomplished was “a big

deal” even describing

his celebrated football

career with the

explanation “All that

stuff was the work of

ten guys out there on

the field with me. I

just happened to play a

position where you got a

lot of credit.” He

battled back from his

stroke to continue his

practice in his former

home town because his

services were needed and

he needed to serve. He

said little or nothing

about being an All

American or the winner

of multiple combat

awards. Swink was a man

of his time and most of

all, everything a man

should be.