TERRY LONG; WHAT'S GOOD, WHAT'S BAD, WHAT'S UGLY

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS July 1 2016:

TERRY LONG; WHAT'S GOOD, WHAT'S BAD, WHAT'S UGLY

By Dr. Ken

WHAT’S GOOD:

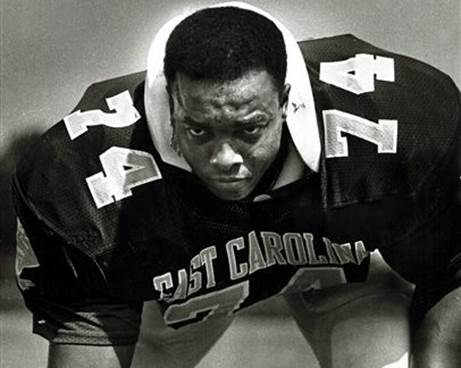

At Euclaine High School in

Columbia, South Carolina, a

young Terry Long was going

nowhere fast on the football

field. Entering his senior

season the 5’11”, 160 pound Long

had few physical attributes to

lend to the squad and no

on-field experience, so instead

returned to a variety of after

school jobs to help support his

widowed mother and six other

siblings halfway through the

season. This truncated season of

varsity football was the

high-water mark of the athletic

career of Long when he left high

school. He joined the United

States Army as so many other

high school graduates do, was

assigned to the 82nd

Airborne and spent two years in

the Special Forces. Three months

into his new life he found the

weight room and dedicated any

leisure time to this new

obsession. Despite logging more

than sixty jumps and running

four to five miles daily, Long

grew a lot of muscle. Akin to

something out of the Charles

Atlas ads, the relatively thin

and definitely under-muscled

Long responded spectacularly to

the physical demands of Army

life and his new weight training

pursuit. By the conclusion of

his hitch, he was no taller but

he had put on almost one hundred

pounds of what appeared to be

solid muscle, played noseguard

on the Fort Bragg football team

that competed in an

intra-service league, and most

impressively, could now squat

with 500 pounds, bench press

405, and deadlift 400. His

forty-yard sprint time was

clocked at 4.8 seconds, he could

perform a standing flip at any

time, and dunk a basketball from

a standing start. He had

survived the rigorous “torture

training” where because of his

size, Terry was usually the

“prisoner” who was punched and

kicked when captured by mock

enemy forces during base

maneuvers and he thrived on it.

In short, Terry Long had

transformed himself from Clark

Kent to Superman!

Now eager to play more

football and pursue an

advanced education, Long

contacted a number of

university football programs

and received scholarship

offers from Nebraska and

Wyoming among others, but

preferred to remain close to

home and family, choosing to

attend East Carolina

University. While the

coaching staff, like

everyone else was impressed

with Long’s physical

development, he had little

in the way of football

technique and knowledge and

later admitted that he had

“spent the first two years

at ECU learning how to play

football.” He did however,

work hard and he learned.

Under the guidance of

legendary Strength And

Conditioning Coach Dr. Mike

Gentry who later established

himself as one of the best

in the profession during his

twenty-nine seasons at

Virginia Tech, Long also

succeeded in becoming

perhaps the strongest

college football player of

all time. Listed at 279

going into his junior season

of 1982, he had improved by

leaps and bounds, touted as

a potential All American on

a very talented squad that

included running back

Earnest Byner. ECU’s 1983

team was often referred to

locally as “The Unknowns” as

few out of the area or

school alumni knew that

twelve players from that

squad would be drafted into

the NFL and two others would

ply their wares in the

Canadian Football League.

Knowing that they had an

unusual physical

specimen in their midst,

the Pirates public

relations department

went full blast to

garner recognition for

the team and

specifically for Terry

Long. Posters peppered

the Carolinas, featuring

Long in swim trunks and

a muscular pose with the

admonition to “Come See

the Strongest Man In

College Football When He

Comes To Your Town,”

harking back to the

circus and carnival

posters of old. Strength

Coach Gentry, himself a

successful powerlifting

competitor, convinced

Terry to enter the North

Carolina State

Powerlifting

Championships where

under official

competition conditions,

Long proved himself the

equal of the top lifters

in the world. His

twenty-one inch neck and

twenty-two inch arms

helped him elevate 837

pounds in the squat, 501

in the bench press, and

865 in the deadlift,

only thirty-nine pounds

less than the existing

world record! With a 441

hang clean and training

lifts of 900 squat, 565

bench press, and 865

pound deadlift and the

addition of a

thirty-four-inch

vertical jump at a body

weight close to 300

pounds, there was no

doubt that this physical

education major was up

to the rigors of pro

football. That he became

East Carolina’s initial

AP Consensus First Team

All American proved that

he also had mastered the

physical skills

necessary to rise to the

next level of the sport.

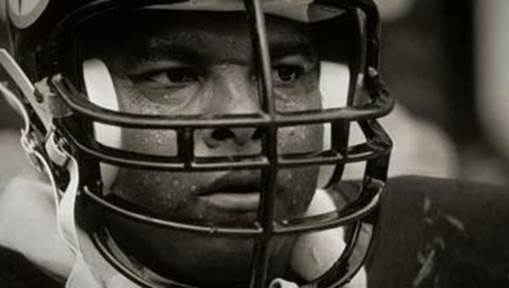

Pro Scouts had told him

had he been three or

four inches taller, he

would have been a first

round draft choice but

instead was taken as the

Steelers second pick in

the fourth round of the

1984 draft. By ’85 he

was a starting guard,

well liked for his easy

going personality, and

donated a scholarship to

East Carolina

University. Long had

overcome a background

fraught with problems

and obstacles to become

a professional football

player, proving that

there was still a place

for unrelenting hard

work and perseverance in

one’s quest to fulfill a

dream.

WHAT’S BAD:

Although the medical

information was already

beginning to come in

about the deleterious

effects of anabolic

steroids, there is no

doubt that the early to

mid-1980s was the zenith

of their use by

professional football

players. It took the

sporting world’s

reaction to Canadian

sprinter Ben Johnson’s

breathtaking

performances at the 1987

World Championships and

1988 Olympic Games and

subsequent

disqualification for

steroid use to bring the

matter to the forefront

of public attention but

there were signs years

before that this was

coming. Another Canadian

sprint athlete, Mike

Dwyer “expressed concern

that the use of drugs

had reached ‘epidemic

proportions’ among

Canadian sprinters” in

1986. Obviously, it is

impossible to procure or

know accurate figures

but those who worked

closely with NFL, CFL,

and USFL players have

placed rather high

estimates on steroid use

among offensive and

defensive linemen. Many

either during that time

period and especially

prior to the NFL’s ban

on and testing for these

performance enhancing

drugs in 1987 admitted

that they used them and

often lamented that “I

have to, if everyone

else is on something. I

have to be able to

compete.”

The

birth of the United

States Football League

no doubt led to a larger

than expected

proportional increase in

anabolic drug use,

unexpected at least, to

the typical fan who

lacks the insight to a

football player’s

emotional drive. Those

who worked in the drug

testing field were

perhaps surprised at

first to find that the

largest numbers of drug

use failures were

recorded for the

smaller, or lower level

collegiate programs when

the NCAA began testing

for drugs. Needless to

state, the players

recruited to Michigan,

Ohio State, Texas,

Alabama, Pittsburgh,

USC, and the other major

powers were the best or

certainly among the best

in the nation. Their

ability, existing size

and strength, and

football instincts

allowed them this

advantage and thus, they

most often did not seek

out the edge offered by

anabolic steroids. Hall

of Famer Anthony Munoz

summed it up well by

stating that he never

used enhancement drugs

because he just didn’t

need them and “felt

sorry for those who

believed they did.” The

Division II player who

was an inch or so too

short, a step or so too

slow, or otherwise not

quite up to the

recruitment standards of

the Big Ten, SEC, or SWC

were more likely to seek

out “something to make

up for their lack of

whatever it was” in

order to realize their

dream of All American

status or a pro football

contract. Despite the

presence of many

exceptional players in

the USFL, the majority

met the criteria for

those “just lacking in

NFL qualities” and in

the professional game,

estimates were made that

drug use was higher

there than in the NFL

itself. In either case,

it was not unusual

relative to the behavior

of a large percentage of

professional football

linemen of the early

1980s to indulge in

anabolic or other

performance enhancement

drug use. Speculation is

just that,

“speculative,” but in

Terry Long’s case, it is

fact that he failed an

NFL drug test indicating

the use of banned

anabolic steroids at the

start of the Steelers

training camp on July

11, 1991. When notified

of the results, Long

attempted suicide and

was admitted to the

psychiatric ward of

Allegheny General

Hospital, either by

“taking some sleeping

pills” or by the more

publicized and reported

ingestion of rat poison.

The truth was worse;

Long had locked himself

in his garage with the

car engine running and

only the quick response

of his current

girlfriend who dragged

him away from the carbon

monoxide saved him. The

next day he ate rat

poison and was

hospitalized.

In what became legendary

head coach Chuck Noll’s

final season, Long did

in fact lose his

starting guard position

to Carlton Haselrig,

starting but three of

the eight games he

played in until the NFL

announced his four game

suspension on November

15th. Thus

ended the eight year

professional football

career of Terry Long;

shamed by the public

revelation of his

anabolic drug use, an

unsuccessful suicide

attempt, and reports by

his teammates of unusual

behavior.

THE UGLY:

Even before the

announcement of his

positive steroid test,

teammates noted a change

in Terry Long’s

behavior. His sudden

mood swings and bouts of

depression were a

contrast to the gracious

“T-Bone” so well liked

by everyone. Already

divorced, he shed

himself of the

girlfriend who had saved

him from his first

suicide attempt,

remarried, and

vacillated between

loving husband and

enraged adversary. He

gave a great deal of

money away to those who

asked and had a

succession of failed

businesses, in part

because he could not

maintain his focus on

any one project for a

sustained period of

time, in part because he

would not leave his home

for days at a time. His

former teammates had, in

his final season, often

referred to Terry as

“Sybil” because of the

many personalities he

flashed in the locker

room. Some in-the-know

attributed his change in

behavior to steroid use,

others were bewildered

but there was no doubt

that Terry Long was no

longer the Terry Long

whom Noll himself was so

fond of. After

retirement, life rapidly

spun out of control. By

March 23, 2005, an

indictment had been

issued, charging Long

with a litany of fraud

related crimes and most

seriously, the arson

that had destroyed his

Pittsburgh based Value

Added Foods chicken

processing plant on

September 23, 2003.

These very significant

charges that carried a

maximum of fifty-five

years in prison and

$2,000,000.00 in fines

augmented an outstanding

Missouri warrant for

passing bad checks in

the Kansas City area.

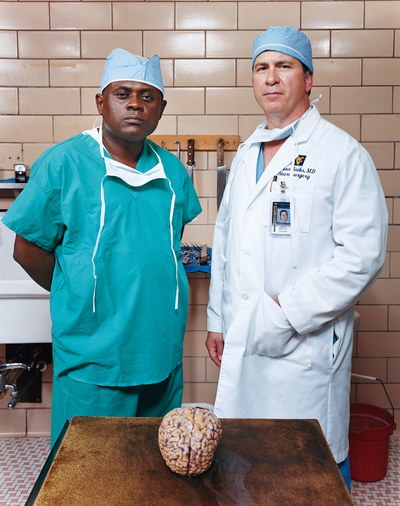

Pathologist Bennet Omalu

and neurosurgeon Julian

Bails examined two

Steelers brains, Long

and Mike Webster, that

began what can be called

“The CTE Movement”

In an era that now seems so long

ago, the time-honored way to

discipline and perhaps

“straighten out” a college

football player who fought too

much, may have been too casual

about class attendance, or was

otherwise a “behavior problem

but a good kid” was to convince

them to join the military for

what used to be the available

one or two year stints, and then

return to school. In most cases,

for those who did return to the

college campus and football

program, the military service

had the desired effect . The

older, more experienced,

worldly, and disciplined

individual was usually able to

contribute to the football team

and campus community in a

positive manner. For others like

Terry Long, voluntary military

service provided the time and

opportunity to become, as the

slogan goes, “all he could be”

and rise to the level of an

effective National Football

League player and starter.

Long “appeared

disheveled during his

(court) appearance” and

could claim only the

$300.00 in his pocket

and a checking account

holding $750.00. His

home was in foreclosure

and he was again facing

divorce proceedings.

Once more he attempted

suicide, drinking a can

of Drano, survived the

ordeal and revisited the

psychiatric ward. On

June 7, 2005, his

attempts to take his own

life were finally

successful, succumbing

to the organ and brain

damage inflicted by

drinking a can of

anti-freeze. As a

suicide, the autopsy was

left to the Office of

the Medical Examiner and

Long, like his teammate

Mike Webster, became the

foundation for the early

studies into what became

christened, Chronic

Traumatic Encephalopathy

or CTE. Chronicled in

books and on film, the

war of words, financing,

ultimate responsibility,

and associated lawsuits,

the many battles of CTE

had former East Carolina

University great and

Pittsburgh Steelers

starting right guard

Terry Long firmly

planted on the ground

floor. To this day, no

one can state with

certainty what belied or

what propelled the

demise of Terry Long,

yet, “what was good” in

his dedication to

literally will his way

onto the gridiron

through his focused hard

work should be

remembered long after

“what was bad” and “what

was ugly.”