WINSTON HILL, THE JETS' ROCK

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS June 1 2016:

WINSTON HILL, THE JETS' ROCK

By Dr. Ken

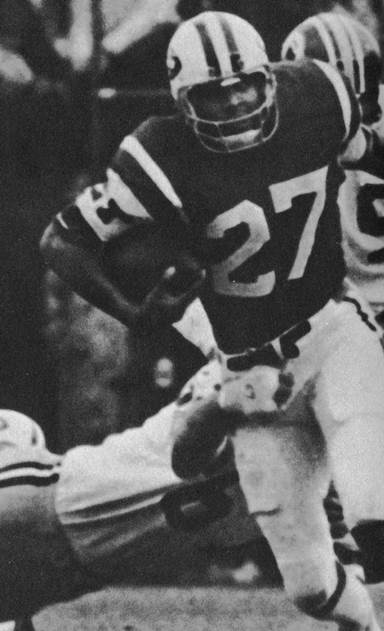

Phil Wise was an

aggressive defensive

back for the Jets 1971

through 1976

Phil was a defensive back

out of the University of

Nebraska Omaha that played

rather well for much of his

career with the Jets. From

1971, after joining the team

as a sixth round draft

choice, through ’76, he

started in the secondary and

played on special teams.

Phil completed his NFL

career with the Vikings from

’77 through ’79 and remained

in the Minneapolis area as a

sports radio personality.

With the Jets however, he

latched onto strength

training as a means to

improve his game, often

teaming up with fellow

defensive back Steve Tannen.

Wise however, was anxious to

mine as much helpful

information as possible and

that included improving his

nutrition. We had numerous

conversations relative to

dietary intake which led to

an attempt to give Phil

recipes so that he could

cook and bake in a

“healthier” manner. It was

quickly apparent that this

would not work and for a

good part of the Jets’

season I would bake low fat

yogurt cheesecakes and

flourless cakes and bring

them to Wise in the Hofstra

facility. Making it clear

that I was not in the bakery

or restaurant business, I

was able to deflect the

friendly pastry requests by

other players but on one

occasion, offensive tackle

Winston Hill asked to speak

to me.

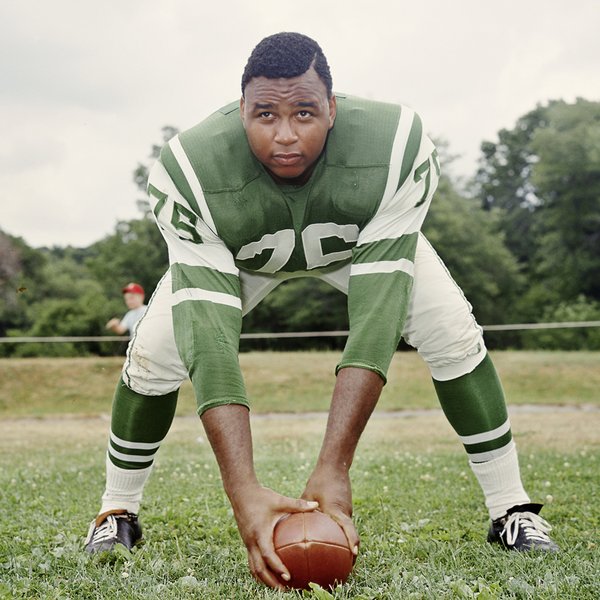

Jets’ offensive tackle

Winston Hill had a

presence that dwarfed

his considerable

physical stature

As noted by Hill’s long-time

friend and Colorado

Congressman Ken Buck,

“Growing up as a black

person in East Texas in the

1940s and 1950s could

destroy a young man's

self-confidence and

optimism, and even limit his

achievements in life. But my

friend Winston Hill never

let racism, bigotry or

adversity stand in his way.

With the support of his

family, his faith and his

friends, Winston wouldn't

allow the world to tell him

who he could or couldn't

be.” Buck also stated, “It

would be understandable if

the bitter taste of

childhood racism and

alienation made Winston a

harsh, unforgiving adult.

Instead, he embodied

kindness, forgiveness and

humility — the man was

fundamentally selfless. He

never had a bad thing to say

about anyone…” Tennis became

an interest and he worked

hard to become a star

athlete on the courts. With

size, strength, and terrific

footwork, however, football

seemed like a natural avenue

to success.

In 1964 Hill established

himself as a full time

starter and in the early

part of his career

primarily manned the

left offensive tackle

position while serving

occasional duty as

center. He was agile and

strong enough to play

any of the offensive

line positions and his

proficiency was rapidly

noticed. In 1965 with

the arrival of

quarterback Joe Namath,

Winston was noticed

enough to be an American

Football League All Star

and from 1967 through

’73, he was named to

either an AFL All Star

or NFL Pro Bowl squad.

His superior play in the

AFL found him named to

the All Time AFL Second

Team. He was almost

immediately recognized

as a gifted pass blocker

and with the famous

Namath to protect,

perhaps it was assumed

that this was his

primary focus. Jets

fullback Matt Snell

stated that Hill was “so

graceful, so beautiful

to watch. Took them just

where he wanted them

(defensive linemen) to

go. Never seemed like he

was exerting himself

that much.” Although his

initial recognition came

as one of the best pass

blockers in the league,

he utilized his great

strength as a dependable

run blocking lineman

also, and of course

received that delayed

recognition after the

Jets Super Bowl upset of

the Colts that saw Snell

gain his primary yardage

behind Hill’s left side

of the Jets offensive

line. “I’ve been telling

reporters for a long

time that Winston Hill

is a great offensive

tackle,” victorious

coach Weeb Ewbank said

after Super Bowl III,

“and (in the Super Bowl)

he proved it. I mean,

when he blocks he

doesn’t just a get a

stalemate with the guy

he’s on. He blows him

out.” Hill’s success was

very much predicated on

the pressure he placed

upon himself to improve

and learn. In 1971,

Hill’s ninth

professional season,

offensive line coach

Wimp Hewgley said,

"Winston is a very

analytical person,

always searching for a

better method of doing

things. He's always

asking if he's doing the

correct thing. If not,

he wants to know why.

It's the kind of thing

you would expect from a

rookie, not someone who

has been around all

these years."

When entering the New York Jets

locker room, one could not miss

Winston Hill. Although large for

his era at 6’4” and 270 pounds,

there were many other National

Football League linemen just as

big or bigger. Yet Hill filled a

room with both his physical size

and the manner in which he

carried himself. Sadly, like so

many of his football

contemporaries, he passed away

this past April 26th

at the age of seventy-four.

Among the many individuals the

author has met or spent time

with, Hill was among the most

memorable.

The author’s personal

circumstances were at one time,

similar to many young people who

have family responsibilities

while pursuing an education.

Concurrent employment in a

number of disparate areas and

school attendance required time

and effort which led to eventual

academic and vocational success.

After working as a lumberjack in

the Solon, Maine area for a six

month period, returning to

school to enhance my graduate

education did not obviate the

need for hard work and a steady

income. Thus backstage and

travel related security work in

the rock and roll industry, iron

work, and applying the skills of

a line cook, all of which could

have qualified as a return to

previous vocations, allowed for

support of the family and a

return to school. The New York

Jets, with their training

headquarters at Long Island’s

Hofstra University placed many

of their players in the Point

Lookout-Long Beach area I grew

up in. In those pre-Yuppie-

gentrification-of-Point Lookout

days, and while the Jets had no

more than a nascent strength and

conditioning facility, a number

of their players gravitated to

our garage gym as well as one of

the very few local commercial

training facilities nearby. Some

of the Jets, with defensive back

Phil Wise among them, had an

active interest in training and

diet.

If there was one member of

the Jets I was uncomfortable

around, it was Hill. One

would think that the great

Joe Namath would be the Jet

that was intimidating to

approach, but Joe offered me

a ride to Manhattan one day,

insisting that I join him in

the front seat of his

Cadillac so that we could

talk. I deferred, feeling

that it was inappropriate to

sit in the front passenger

seat while the much taller

Tannen and Wise jammed

themselves into the rear

seat. Joe immediately put me

at ease by saying, “I see

you around all the time,

you’re the lifting guy. Tell

me some things about

yourself so I can know you.”

This was unexpected yet

highly appreciated and

Namath’s complete lack of

“celebrity” in his private

time was revealing and

predicted the same type of

unpretentious behavior in

any other personal encounter

or conversation I had with

him from that moment

forward. Winston Hill

however, was always a true

presence and despite being

reserved, had a quiet

strength and dignity about

him that was exceptionally

powerful and yes,

intimidating. I had been

told by everyone connected

to the team that Hill was

“the man,” “definitely a

leader,” and the word

“great” prefaced many

descriptions of the skilled

offensive tackle by

teammates and coaches, but

his palpable aura put me on

edge. Wise told me that Hill

wanted to talk with me and I

almost felt as if I was

repeating my frequent trips

to the high school

principal’s office.

Any concerns I had about

Winston Hill were quelled in

our first conversation. He

had questions about

conditioning and what I

found in subsequent

discussions was a man of

deep thought who had lived

through what I would have

considered a difficult and

frightful upbringing. Having

hitchhiked from New York to

Baton Rouge, Louisiana and

working briefly in both the

Gulf of Mexico and along the

“East Texas Corridor,” I had

but a glimpse of the racial

divide that existed in the

1960’s and previous decades.

Hill grew up in Joaquin,

Texas and attended the

segregated Weldon High

School in Gladewater where

his father Garfield was the

school principal. Gladewater

is approximately twelve

miles from Longview, the

site of one of the

Southwest’s worst race

riots. The racially

motivated dragging death of

James Byrd Jr. in Jasper and

the racist reputation of

so-called “Sundown Towns”

like Vidor marked the east

Texas region of Winston

Hill’s youth. Hill dealt

with prejudice by doing his

best, by excelling, and by

taking on every challenge

with dignity and purpose.

The absence of a youth

football program due to

segregation and Winston’s

desire to play pushed his

father to start a team and

Hill overcame his asthma and

a heart defect to become an

outstanding player at Weldon

High School. With

segregation again allowing

for limited options in the

South and Southwest, Hill

accepted a scholarship offer

from historically Black

Texas Southern University in

Houston and entered as a

member of the freshmen team

of 1959. His understated

toughness, intelligence, and

willingness to work hard

enough to do everything as

well as possible as a

two-way linemen, led to NAIA

All American and All

Southwest Athletic

Conference honors. He was

drafted in the eleventh

round of the 1963 draft by

the Baltimore Colts but

released in the pre-season.

With former Colts head coach

Weeb Eubank the new mentor

of the remodeled New York

Jets, Hill was yet another

of a number of “former

Colts” that were embraced by

the previous Titans team

that was being rebuilt in

Eubanks’ image.

Through his fourteen

seasons with the Jets

which included his

rookie season where he

did not step onto the

field during a game,

Hill compiled a streak

of 174 consecutive

starts, the tenth

longest in pro football

history. When Namath

went to the Los Angeles

Rams for the ’77 season,

Hill went with him and

they both retired

afterwards. Winston Hill

could then look back and

view a lengthy list of

achievement: induction

to the Texas Southern

Sports Hall Of Fame;

selection to four AFL

All Star Teams and the

Second Team All Time AFL

squad; a member of the

Jets All Time Four

Decade Team and

induction to their Ring

Of Honor; the Jets

retirement of his number

75 jersey.