VIRGIL CARTER, "THE BLUE DARTER" OF BYU

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS January 2016:

VIRGIL CARTER,

"THE BLUE DARTER" OF BYU

By Dr. Ken

I am admittedly an old guy

with old fashioned values. The

three part series that ran

recently within the HELMET

NEWS/REFLECTIONS area of

HELMET HUT

(http://www.helmethut.com/newsindex.html,

September, October, and November

2015 columns) offered numerous

reasons and what could be

construed as complaints,

explaining the relative demise

of the modern game. A topic not

broached, was a strongly held

opinion that college athletics

are for student-athletes, not

pay-for-play athletes. Like most

college students of the 1960’s,

I held a variety of jobs while

attending classes, with the

additional responsibilities of

lifting weights, constantly

running, and both practicing and

playing football. My employment

included filling the roles of

manual laborer, ironworker,

bouncer, short order cook, truck

driver, and night time office

cleaner/janitor. My scholarship

included the early morning

and/or late night

responsibilities in the

university vivarium as the

animal feeding and waste removal

expert. Simply put, I was the

student in charge of feeding and

cleaning the cages of all of the

monkeys, chimps, gibbons,

coatimundis, and cabybaras

(100-140 pound rodents that live

in the riverbeds of South

America) that were used for drug

related experiments in the

science labs. My compensation

equated to perhaps $10.00 per

hour at today’s rates.

HISTORICAL INSERT

Reading the above paragraph,

bemoaning the fact that as a

typical college student, even

one with the benefit of

scholarship money, I was

relegated to a succession of low

paying and menial jobs in order

to pay bills, there is another

side to the facts. As a bar or

club bouncer, I was paid the

standard minimal wage the

industry offered for the

privilege of tossing drunk and

unruly patrons from the premises

and I did this at a number of

establishments. However,

eventually working my way up to

the point that I directed

backstage security for a number

of rock bands and on a regional

basis for Motown Records tours,

worked for Bill Graham, and

served as an off-stage personal

bodyguard for known rock and

roll industry celebrities, I was

paid exceptionally well for the

time put into the endeavor. My

close and late friend Joe Tuths

handled the West Coast security

for the first three Led Zeppelin

tours, calling me to offer,

“free room, board, and travel,

$1000.00 per week in cash, and

all of the drugs and alcohol you

want.” As a teetotaler, I

obviously passed on the latter

inducements as he knew I would,

but for the era, the rest was

big money and I signed on. Made

worse by Zeppelin’s own, “in

from Great Britain” personal

security force and manager, we

had our hands full but there was

money to be made in the business

from the late 1960’s through the

mid-1970’s. Other former

football players like Bob “Mr.

Goodbar” Bender, a University of

Buffalo transfer slated to play

middle linebacker at Kent State,

instead left for a security job

with the Rolling Stones,

fortuitously vacating the

position for an up-and-coming

Jack Lambert.

|

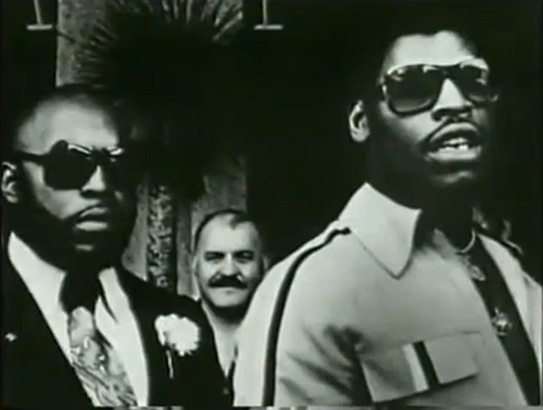

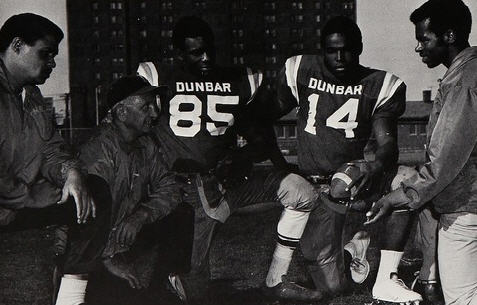

The captain of the 1969 Dunbar Vocational High School team in Chicago was Laurence Tero, number 14

Perhaps the most well-known

football player turned

bouncer from that same era

was Laurence Tero of

Chicago. The star of Dunbar

Vocational High School’s

successful 1969 football

squad, Tero was a 6’1”, 195

pound two-way back who had

been the league wrestling

champion at 165 pounds his

junior year. Encouraged to

lift weights by his older

brothers for the express

purpose of better protecting

himself in the exceptionally

impoverished and dangerous

neighborhood he and his

eleven siblings lived in,

Tero earned a football

scholarship to Prairie View

A&M University but was

expelled after his freshman

year.

Utilizing his enhanced-to

235 pounds muscular size,

strength, and a great deal

of natural charisma, he

became an effective and

exceptionally professional

bouncer at Chicago’s busiest

and most dangerous dance

clubs and a personal

bodyguard for celebrities

visiting the city. Building

a nationally known

reputation, Tero altered the

spelling of his name to

Laurence Tureaud. I met him

when he served as the

personal bodyguard for

heavyweight boxing champion

Leon Spinks. For those who

lived in or around Leon’s

hometown of St. Louis, the

late 1970’s and especially

during his brief reign as

champion after defeating

Muhammad Ali on February 15,

1978, provided almost daily

proof that Leon needed

Tureaud’s assistance and

protection. What seemed like

a succession of Leon’s new

cars were reported as stolen

after being found wrapped

around telephone poles or

trees throughout the St.

Louis area in the early

morning hours, with Leon

always claiming that he

“didn’t know nothin’” about

such events. Leon and/or his

brother Michael had

disagreements, arguments, or

true legal battles with

local police on what seemed

like a regular basis,

sometimes involving more

serious infractions and

others, simple but illegal

acts such as parking on the

sidewalk of the St. Louis

Airport terminal because “it

was the only available

space”! Not having yet

changed his name once again

from Tureaud to “Mr. T,” he

had, due to his work with

Spinks, actor Steve McQueen,

and others of that stature,

elevated his daily fee from

$500.00 to $3000.00 per day!

Tureaud was quick to donate

part of his winner’s fee

from the World’s Toughest

Bouncer Contest to his

church and was always

involved with improving the

life of children who were

growing up in the same type

of social and economic

environment he had survived.