THEY USED TO CALL IT FOOTBALL, PART THREE

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS November 2015:

THEY USED TO CALL IT FOOTBALL, PART T

HREE

By Dr. Ken

One can run, do specific football related drills, lift weights, and even include contact against a hand held bag or sled in order to prepare for their upcoming football season. One of the great truths of football that is learned as early as high school and which becomes emphasized at the collegiate level, is that you can be in great “condition” but you cannot be conditioned to block and tackle until you block and tackle. The only way to become conditioned to the contact is to hit and be hit, to be exposed to actual contact. Before the start of sixth grade I became aware that there was a core group of athletes in our area that spent summer evenings running, throwing a football, and doing what appeared to be specific football type of drills during the evenings. They would meet three or four times each week on the beach or at the high school field and work hard for approximately ninety minutes or until the darkness made it difficult and a bit hazardous to continue. The group varied from eight to eighteen or more on any evening and some remained a part of that group of trainees for a number of years. They had attended different high schools with some playing at large college programs, some at smaller ones and others at what were still nationally respected Ivy League programs. A few would bring teammates to the sessions, these “outsiders” presumably visiting for a short time but who enthusiastically jumped into the mix of sprinting up and down sand dunes, running in knee or waist-deep ocean water, doing “fireman’s carry” in the soft sand, and a few years later, when our younger group became incorporated into the main group, a drill we referred to as “Hamburger” which was no more than the standard Oklahoma Drill done without protective equipment.

All of us lifted weights when it

was still a shunned or

negatively interpreted activity,

and all of us were strong

relative to bodyweight and

certainly presented at our high

school, college, or pro camps in

superior physical condition when

compared to most of our

teammates. Yet, every one of us,

when we first saw or spoke to

each other after the

commencement of fall camp, would

comment that our level of

soreness after the hitting

began, was equivalent to that of

our teammates. We could run

further and drill longer than

anyone, we were strong, and by

every measure we were

“well-conditioned,” but when the

contact came, we suffered the

same two or three days of

extreme soreness from the actual

contact. It was a harsh reminder

that you needed to be hit in

order to be conditioned to be

hit! It really was that simple.

HISTORICAL INSERT: Lou

DeFilippo, Jr.

|

Lou “Babe” DeFilippo, Jr. Purdue’s 1962 Big Ten Sophomore Of The Year

For many years the number

of Division 1 football

players recruited from New

York State has been

constant, averaging a bit

less than twenty-five per

season. In years that

Syracuse has been more

successful in their in-state

recruiting, the overall

number increases but most

college coaches will quickly

state that they place their

focus onto the northern New

Jersey area long before they

venture into New York State.

Of those approximately

twenty-five scholarship

players, three to six will

hail from Long Island. This

number too has been constant

with the involved

universities varying,

dependent upon which

assistant college coaches

have connections in the

region. Legendary Amityville

High School coach Lou Howard

produced powerhouse teams

throughout the 1950’s and

‘60’s, featuring great

players like Bernie Wyatt

and John Niland who both

attended Iowa. Predictably,

both were outstanding

players at Iowa. Niland was

later an All Pro offensive

lineman with the Dallas

Cowboys while Wyatt became a

long time assistant coach at

his alma mater and then at

Wisconsin under Barry

Alvarez. When Wyatt was a

position coach and

recruiting coordinator at

both schools, they had

numerous Long Island and New

York/New Jersey Metropolitan

players on those squads due

to Bernie’s many contacts in

the area. Purdue University

too regularly recruited a

number of Long Island

players between 1960 through

the mid-1970’s. Unlike some

of the players recruited to

Iowa by Wyatt who later

became “name players” like

Niland or twelve-year NFL

veteran and first round

draft choice Ronnie Harmon,

Purdue focused on solid

players who for the most

part, became integral parts

and multi-year letter

winners of what were

terrific offensive lines.

Sal Ciampi who has been

mentioned in numerous HELMET

NEWS/REFLECTIONS articles

has been perhaps the best

known locally, receiving

national recognition as a

record setting high school

coach following his

outstanding Purdue career

that included being the

third Boilermaker to be

named as an Academic All

American, and as an All Big

Ten selection who captained

his squad and then had an

outstanding Blue-Gray Game.

|

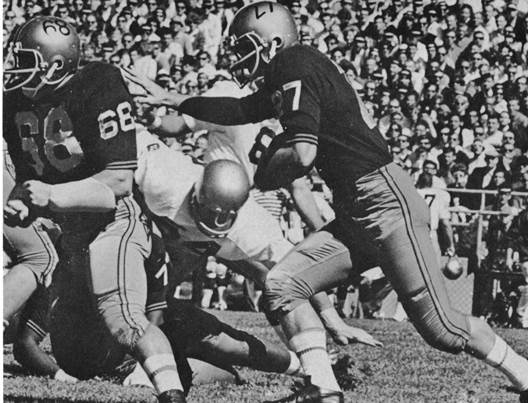

At only 5’9” and 201 pounds, few hit as hard and consistently as Salvatore Ciampi of Lawrence High School. Sal was a workout warrior, often setting the pace in the local garage where a number of collegiate and high school players gathered to lift weights over the summer. Here he leads Purdue back Gordon Teter against Notre Dame. Sal is revered as one of Long Island’s greatest high school players and coaches

Though more

standouts like Gary

and Henry Feil would

follow and well

represent the

Boilermaker

offensive lines, a

contemporary of

Sal’s perhaps had

the most potential

to be an all-time

great. Lou DeFilippo

Jr. of W. Tresper

Clarke High School

certainly had an

example to follow,

one that lived in

his own house. His

father, Lou

DeFilippo had been

the leader of his

Hillhouse

(Connecticut) High

School team that won

the state

championship, a

center on the very

good Fordham teams

of the 1930’s, and a

member of the N.Y.

Giants in 1941 and

following his

military commitment,

again from 1945

through ’47. He

later coached with

the Baltimore Colts

and at Fordham and

Columbia

Universities. A

teacher at heart, he

followed his college

and pro work with a

life of high school

teaching and

coaching, first at

Long Island’s Clarke

High School and then

as head coach at

East Meadow where

from 1961 through

’67 he compiled a

46-9-1 record that

included a number of

championships. He

made his lasting

mark returning to

Connecticut to coach

Derby High School

from 1968 through

1982, going

116-30-8, having

five undefeated

teams, and winning

state championships.

This revered molder

of men spent part of

his World War II

military service

time playing

football at Purdue

University and this

is where he steered

son Lou Jr. who had

his choice of

numerous colleges.

“Babe” as younger

Lou was often

referred to, was a

5’9”, 235 pound

block of muscle who

also spent the Long

Island summers

running and lifting

and it paid off his

sophomore season of

1962 when he was the

Big Ten Sophomore Of

The Year and named

to a number of All

American teams at

tackle.

With more stardom

forecast, he was

derailed for the ’63

season after a May

25, 1963 auto

accident that

resulted in a severe

injury to his left

arm, costing him a

redshirt season. He

returned and started

for the Boilermakers

at left tackle for

the 1964 and 1965

seasons on the

opposite side of the

line of Ciampi, his

high school rival.

Like Sal and his

father, Lou Jr.

became a highly

respected and much

beloved high school

teacher and coach

before passing away

at a relatively

young age. The work

put in over the

summers accurately

predicted the

success that came

once the season

started for Lou and

a dedicated group of

Long Island athletes

from a past era.

As a logical

thinker, the formula

for today’s game of

football and its

appalling lack of

fundamentals related

to blocking and

tackling is a rather

easy one:

Lack of time dedicated

to football related

activity due to NCAA

limitations +

Lack of allowed contact

during every aspect of

NFL related activity as

mandated by the

Collective Bargaining

Agreement =

Lack of proper blocking and tackling ability and techniques.

I only wish that my physics classes had been this simple! I would like to repeat that hard core football fans and especially Fantasy Football Fans (please allow me to more accurately describe that as “Gambling Football Fans” who may know statistics but don’t necessarily know “football”) marvel at the “skill,” size, speed, and athletic ability of today’s player but coaches at every level complain that the game has changed, not because it is “softer” but because there is such a dearth of fundamental teaching and learning. The reminders are everywhere. While watching a segment of Inside The NFL, commentator Phil Simms, in what had to be no more than a short paragraph of verbiage had it been in written form, made at least three references to a defender on screen, making “a form tackle.” This so-called form tackle, to anyone who played the game in the 1950’s through the mid-1970’s, was no more than “a tackle,” what used to be a “regular,” run of the mill, every play, put-your shoulder-on-the-ball or between the numbers, wrap up, and drive tackle. This was truly a “no big deal” tackle, yet Simms’ ongoing, gushing description made one immediately realize that this truly was a “form tackle,” one made in accordance with proper technique where the player broke down into a tackling stance, made contact, wrapped his arms around the ball carrier, and drove his opponent to the ground. It is now indeed a big deal, as routine as it would have been in a previous era, simply because no one does it any longer or at least it is no longer done with frequency.

Respected football writer Bucky Brooks, a former NFL player, noted soon after the passage of the NFL CBA, all of the predictions that have become reality. On August 10, 2011, Brooks wrote,

“Gone are the

grueling two-a-day

practices that have long

been a staple of

training camps. In their

place, teams are able to

conduct one full-contact

padded practice per day

accompanied by a

walkthrough period. The

league has also placed

limits on the number of

full-contact padded

practices during the

regular season. Teams

are permitted a total of

14 for the year with 11

of those practices

conducted during the

first 11 weeks of the

season (a maximum of one

per week)… The loss of

full-contact practices

could rob them (teams

built upon physical

aggressiveness) of the

edginess that allows

them to bully

opponents.”

What passes for “typical

practice attire” in today’s

game of football

Most telling was his

statement that now

clearly echoes what NFL

coaches especially are

lamenting; “They assert

the lack of contact will

leave their squads

unprepared for the

intensity and

physicality of the

game.” I can only say

“Absolutely.” The

predictions for

deterioration in contact

related skills were

obvious. Brooks, Mark

Maske, and others spent

time writing and talking

about this:

One of the important

statistics that needs to

be discovered is the

comparison of head and

neck injuries relative

to knee and lower

extremity injuries.

Maintaining a focus on

protecting the head and

cervical spine is

certainly positive but

if a defender defines

the lower body and

especially the knee area

as “a safer hit” that

will not get them

ejected or earn a

fifteen yard penalty,

then what? The fact is

that defenders have,

since the inclusion of

the most recent CBA

enforced rules,

complained that “there

is no safe place to hit

an offensive player.”

They are penalized and

criticized for hitting

high and risking or

incurring an opponent’s

head injury, and

penalized and criticized

for hitting low, viewed

as “trying to take his

knee out.” An injury

comparison relative to

pre-CBA days could be

revealing.

The bottom line is this,

in my limited opinion:

the game is sloppy, not

well played, and

certainly not “the

physical ballet”

performed by masterful

athletes that the NFL

Network and ESPN would

have the public believe;

it is not yet proven to

be safer relative to

long term injury

compared to the “old

rules” days; the lack of

time and absence of

practice contact has

produced poorly executed

techniques or a lack of

proper and safe

techniques in blocking

and tackling that

perhaps have led to an

increased rate and/or

severity of injury. It

is not certain that the

National Football League

or NCAA would provide an

honest statistical

analysis in either case

as they seem content to

live off of the

marketing emphasis of

the “big hit” and public

perception that they

have produced a safer

game.