THEY USED TO CALL IT FOOTBALL, PART TWO

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS October 2015:

THEY USED TO CALL IT FOOTBALL, PART TWO

The September 2015 HELMET NEWS/REFLECTIONS column included the following:

By Dr. Ken

“Allow me to interject that the

author and the entire staff of

HELMET HUT

agrees that the physical safety

and well-being of every player

is, and must be the foremost

consideration in presenting

every aspect of the game. That

however, puts the following

question squarely in the

forefront of what must be

addressed regarding both the way

in which the game is played

relative to the ‘old days,’ and

what is best regarding player

safety: ‘Is the new game of

football the way it is played

and practiced more conducive to

long term injury and the

production of potential brain

damage compared to the way it

used to be?’”

|

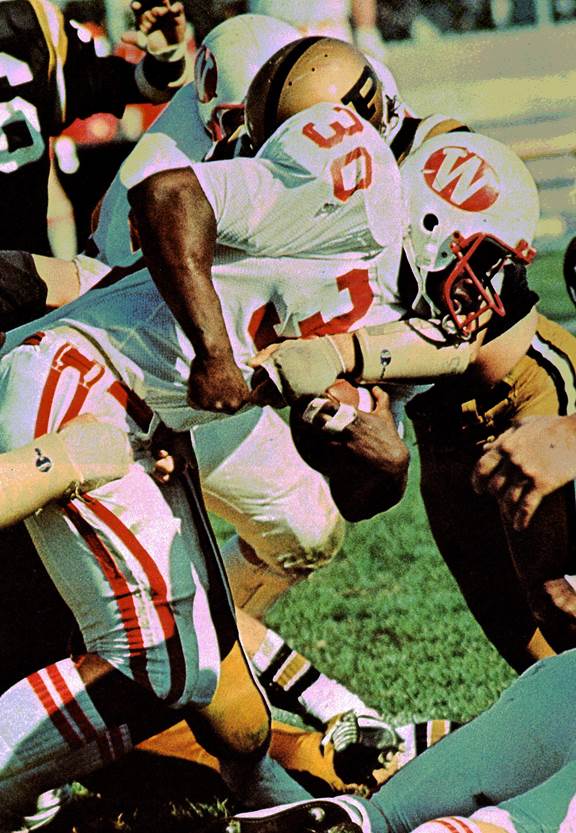

Wisconsin’s Larry Canada faced a lot of weekly tackling in practice in 1975. Facing off full speed versus Purdue was just “business as usual,” unlike today’s game of football with its limited game preparation contact

The number of debilitating

brain related, catastrophic

cervical spine, and head

injuries suffered by the

previous two generations of

football players is the

constant reminder that the

health of players at all

levels must remain the

priority of the game.

However, like other areas of

our culture that have been

altered through the past

three decades, have we

created a situation that now

produces an increased number

of injuries? As a former

player who competed with

extremely limited ability

and football talent relative

to my peers, I was exactly

the type of player most

prone to injury. Those with

a great deal of football

and/or athletic talent can

perform at their best and

usually still perform well

when they are below their

best. If injured, they know

they can “sit” and take some

time to either heal or

return to feeling their best

before resuming their

on-field practice and game

responsibilities. Players

like me did not have that

luxury. Fanatically lifting

weights from the age of

twelve when few athletes

lifted weights and most

coaches discouraged the

activity, and pushing my

muscular weight-to-height

ratio to its absolute limit

was a necessity. I did not

view this as unusual, being

part of a group of lifting,

running, and fitness

devotees who were well aware

that we needed to do

whatever was possible to

make up for a lack of

athletic ability. If

injured, we would not leave

the field, we would not

allow any indication of

injury, and we would most

often not seek the advice or

treatment of any team

related personnel. For me,

this became a habit that was

more or less encoded in

junior high school. It was

not borne of toughness but

rather, fear and insecurity,

having a certainty that once

taken off of the field I

would never be allowed to

return. Those players that

fully understood their

limitations and were willing

to put up with a degree of

bodily damage were most

prone to eventual long term

dysfunction.

|

|

Concussion and broken bones that involved “minor” body parts like the fingers, hands, and forearms could be ignored and disguised. Being unconscious for a minute or two was still considered “a ding,” perhaps a “major ding” but no more than a brief interruption to an immediate return to the field during practice or games. Obviously, this holds the potential for serious and unrelenting health related problems later in life. It is certainly positive that steps have been taken to improve the equipment as well as practice and play procedures in an attempt to prevent recent players from suffering similar damage. That said it is also true that to play football safely and effectively, one must attain a certain minimal level of fitness, specific conditioning, strength, and resiliency before they begin the year’s participation. Despite the complaints of many old timers that “the game just isn’t the same,” the author and staff of HELMET HUT are in agreement that any rules changes that better serve to protect the head and neck are positive. The change in tackling procedures that were mandated in 1976 after a series of lawsuits against helmet manufacturers [see HELMET NEWS/REFLECTIONS February –December 2004] were proven to reduce the number of head and cervical spine injuries suffered on the field.

However, this leads to the question we have proffered for this month, and one that the inordinate number of National Football League pre-season injuries shines a light on: has the intent to protect the players by limiting mandatory team related drills, strength training sessions, and contact in practice now led to a proliferation of injuries due to a lack of appropriate physiological preparation? To my knowledge, no legitimate studies have been done to determine if for example, the number of injuries significant enough to miss regular season games suffered from the beginning of camp through the first two games of the season, are now more or less than those suffered within the same time and game frame of ten or fifteen years ago? Are the collective bargaining agreement and other medically related mandates passed down as “normal operating procedure” preventing or causing injury to NFL players? “No one tackles any more” is a common complaint and observation of fans, scouts, and coaches at all levels. In truth, pro coaches in private discussions have observed this for a number of years. It is agreed that there just isn’t enough allowed time given to general contact drills and specific tackling drills to expect players to tackle effectively or consistently well. Observation of any pro training camp would shock the typical fan once they noted the very obvious lack of contact of any type!

I believe it is “common knowledge” that the quarterbacks entering the NFL in the past few seasons are not prepared to play the professional game. Certainly media reports that a specific quarterback “has never taken a snap under center” and that some “haven’t even huddled since high school” are now old news. Pro coaches understand that coming from systems that are far different than what is represented by the professional game make even the most talented collegiate quarterback a “project.” Not understood by the general football public is that even the best offensive linemen, including All Americans, do not know how to block by NFL standards. It might be obvious to state, “His team throws the ball seventy times a game” or “They don’t run enough for him to run block well, he doesn’t have the experience”, but in truth, many if not most offensive linemen in college cannot pass block either. Skeptics will huff and puff and note that on its face, this seems like a ludicrous statement but collegiate linemen, as a general statement, know how to screen opponents or get their body in the way of an onrushing defender, but less frequently, year by year in the game that is played now, understand how to truly pass block. Their relative lack of consistent contact in practice periods also limits their application of proper on-field techniques. Thus, while we accept that a quarterback who has been in a spread system throughout high school and college may take years of re-training, so do offensive linemen. The equivalent of teaching new techniques to counter defensive players with great athletic ability also means that these individuals are not physically prepared to play at the highest level. This too contributes to the inordinately high rate of injury.

|

Buffalo Bills Guard Richie Incognito came out of Nebraska with run blocking skills and remains one of the best maulers in the NFL, with a full understanding of run game blocking

Limited exposure to necessary professional positional techniques, a shortage of mandatory strength and conditioning sessions, an absence of individual or team contact opportunities prior to the actual game experience, and the heretical statement that many professional level players are “just not that good” relative to the much more limited numbers that had job opportunities when there were fewer teams and smaller rosters have all made for an increasingly dangerous game. Are there viable solutions?

More Next Month