THEY USED TO CALL IT FOOTBALL, PART ONE

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS September 2015:

THEY USED TO CALL IT FOOTBALL, PART ONE

By Dr. Ken

The suspension helmet era in

football is generally considered

to span from the years of

approximately 1945 through the

beginning of the 1980’s.

Technically, that may not be

correct, with the Riddell

suspension helmet developed in

1939 and the various individual

“cell type” internal protection

helmets having widespread use by

the mid-‘70’s. However, it

wasn’t until the mid-1940’s that

full teams would be equipped

with the Riddell RT suspension

helmets on a regular basis and

there were many players with

lengthy careers who wore their

trusty RK or TK suspension

models deep into the Seventies

and some into the early 1980’s.

During that time period, the

specific offensive and defensive

philosophies and formations

changed, and alterations in the

equipment worn and rules of the

game followed to accommodate

those changes. However, the

fundamental purpose of football

remained and the emphasis was on

“the physical,” the dynamic that

allowed players and fans of one

distinct era to relate to those

from other eras. Now, it is

different, everything is

different. Every football fan

who reads the material or

browses the many helmets on our

HELMET HUT

site is interested enough in

football to know that on every

level of play, the game is not

the game that was played in the

1950’s through the late-1970’s

or early ‘80’s.

|

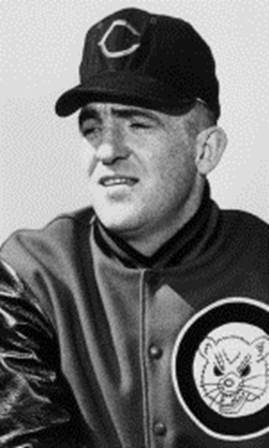

Throughout the 1950 – 1980 span of time, the emphasis in the sport of football was always placed upon blocking and tackling fundamentals. University of Cincinnati tough guy Jim Swanda learned the effective way to tackle “through” the opponent

When the forward pass was introduced to the game, purists were concerned about the demise of football as they knew it. Needless to state, the game became an improved version of its past: more excitement, more scoring, more entertaining and little dilution of the game’s fundamentals. The game was built upon the fundamentals of physically dominating others with blocking and tackling techniques. The proper application of the appropriate technique could allow a smaller and perhaps less imposing individual to defeat another in a one-on-one confrontation and because that possibility existed, the game was always worth watching. As a young high school coach, I annoyed some of the older coaches in our area with an oft-repeated statement I made to my players at the beginning of each season. In summary I said, “Fellows, we think of football as a team game and you certainly must operate as a team in order to successfully execute each play, but what we have is eleven individual match-ups. This makes football an ‘individual game’ too. If I can teach you how to win six or seven of those individual contests on each play, we will win as a team.” In truth, that was the game of football as I knew it and as it was taught by my high school and college coaches, almost to a man, veterans of military combat in World War II, the Korean War, or both. These men had lived through and understood survival situations and brought that sense of conflict, urgency, physical and mental toughness, and willingness to both physically and technically prepare for conflict. The conflict of football, then, was very much a one-on-one, man-to-man battle based on contact, that spanned sixty minutes. If this sounds too testosterone-drenched for the younger reader, this almost perfectly reflects the lack of understanding of the game “then,” versus what football is today.

HISTORICAL INSERT

|

Typical of the way in which football was played from the late 1950’s through the 1960’s when I was of age to play it, were the men who coached the game during that period of time. Very much typical of these men was Richard MacPherson who was in every sense of the word, a “man’s man.” A product of Old Town, Maine, he played four years of football and basketball and two seasons of baseball in high school. His leadership ability stood out, combined with a toughness that reflected being one of twelve children who always had a variety of jobs to supplement the income of his father who worked as a plumber. He had excellent football ability but it was his leadership skills that earned the respect of his teammates. After attending Maine Maritime Academy, he left to enlist in the U.S. Air Force during the Korean War. Four years of military service and the GI Bill brought him to Springfield College with enhanced “command presence,” especially as a more mature student relative to his teammates, and he led as Co-Captain from his center and middle linebacker positions. His teams were exceptionally successful, with Dick calling defensive signals, a true coach on the field. One of Springfield’s assistant coaches noted Dick’s great leadership ability and stated that “he got such high respect from the team. He gave them a lot of confidence in those years.”

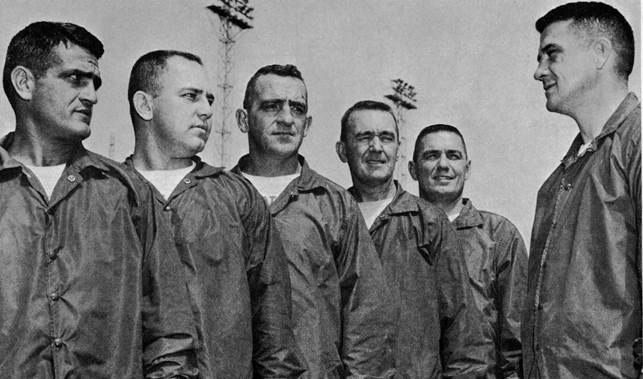

Mac became an assistant at Springfield upon his graduation and then served as a graduate assistant at the University of Illinois where Chuck Studley was an assistant coach. MacPherson moved to an assistant’s position at the University of Massachusetts, and helped to bring Studley in as the head coach there when a coaching change occurred. After a year at UMass Studley took the Cincinnati head job, calling for Mac to join him there as his defensive coach.

|

Head Coach Chuck Studley on the far right, Defensive Coach Dick MacPherson in the middle, with the rest of the 1965 UC staff

Studley too was a military

veteran, a U.S. Navy

submarine torpedo operator

and at UC, their backgrounds

of discipline, organization,

and teamwork was reflected

in the way in which the

fundamentals were taught and

practiced. This was typical

of the times, and of course,

both men rose through the

coaching ranks, with Studley

eventually a defensive

coordinator for Super Bowl

teams with the Bengals and

Dolphins and the head coach

of the Houston Oilers, and

Coach Mac becoming a College

Football Hall of Fame member

after his years as the head

man at Syracuse. Although

Cincinnati has been

considered to be the first

major college to institute

the use of a gap defense

under Coach Mac and Studley,

it was less the innovative

approach to formation and

more the consistent emphasis

on blocking and tackling

that marked the success of

their squads.

Another maxim about the way

in which football used to be

played, was “It isn’t a game

for everyone.” I held great

respect for my teammates,

opponents, and every young

man that I had the privilege

to coach over a combined

eleven-year high school

coaching career, at two

schools. In “my day”

football was not a game for

everyone because if it was

practiced and played

correctly, one would have to

accept the fact that they

would be hit and have to hit

someone else every day. This

is what separated those that

played from those that did

not. There were terrific

athletes in every school

that excelled in other

sports but did not, or could

not play football. It just

“wasn’t for them” and

sometimes it wasn’t for them

in large part because they

did not want to be hit or in

turn, hit someone, every day

of practice and in every

game. Allow me to interject

that the author and the

entire staff of

HELMET HUT

agrees that the physical

safety and well-being of

every player is, and must be

the foremost consideration

in presenting every aspect

of the game. That however,

puts the following question

squarely in the forefront of

what must be addressed

regarding both the way in

which the game is played

relative to the “old days,”

and what is best regarding

player safety: “Is the new

game of football the way it

is played and practiced more

conducive to long term

injury and the production of

potential brain damage

compared to the way it used

to be?”

|

Is the emphasis on playing “basketball on grass” with a desire to avoid basic blocking and tackling and instead try for the ESPN highlight-reel kill shot causing more injuries than it prevents? These most provocative questions have a number of concepts to be considered but there is a crying need for an unbiased study to determine for example, if the new National Football League Collective Bargaining Agreement ‘s dictums regarding allowable practice time, contact sessions, tackling and blocking rules, and voluntary versus mandatory training and preparation sessions are reducing or increasing player injury and potential long range damage

More Next Month