BOB DEVANEY AND HIS CORNHUSKERS, PART TWO

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS July 2015:

BOB DEVANEY AND HIS CORNHUSKERS, PART TWO

By Dr. Ken

The first thing Devaney

discovered upon his arrival in

Lincoln, was a Nebraska program

in a state of disorganized

chaos, but one that had talent.

Assistant coach George Kelly who

was at Nebraska in 1961 and

remained there with Devaney from

’62 through 1969 until leaving

for the Notre Dame staff, said

that Devaney “was amazed at how

much talent there was and he

knew exactly what to do to

organize it. He always seemed to

be playing people in the right

positions.” Unlike some of the

successful coaches of his era,

he also got a lot of work from

his players because they enjoyed

playing for him. Kelly stated

that “…the key things were his

recruiting and the way he gets

along with people. Everybody

likes him. The kids liked him.

He would just go into these

small towns in Nebraska and sit

in the bars and entertain

people.” As a testament to his

players’ feelings towards him,

at a luncheon prior to the 1969

Sun Bowl, he was given a three

minute standing ovation by his

own players! During the

tumultuous times of the ‘60’s,

with many football programs

wrestling with the demands and

assimilation of African American

players, Nebraska residents

found that their head coach was

indeed blind to the color of his

players with a well-earned

reputation for fairness. He

actively recruited African

Americans from New Jersey, from

the south, and from California.

When these same players formed a

Black Caucus in the late ‘60’s

to request that the staff

acquiesce to a list of

suggestions, they found that

there really was nothing to ask

for, Devaney already treated his

players fairly and without

prejudice. One former player

summed it up by stating, “You

would absolutely die for Coach

Devaney.”

|

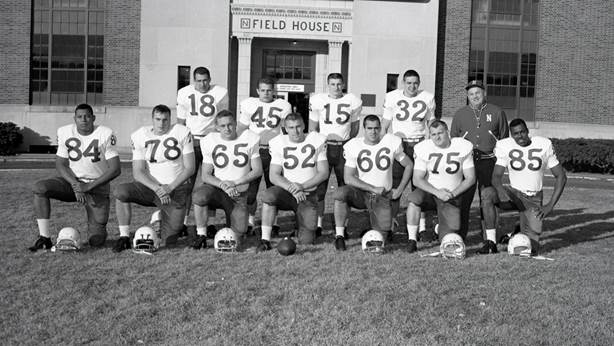

By 1965 Devaney had solidified Nebraska as a program to be reckoned with and donned them in distinctive uniforms with immediately recognizable stylized numerals

As it was at Wyoming, Devaney and his staff out-recruited the other programs in the area. Realizing that many of the state’s players had potential but needed time to adapt from the eight-man football game played in many parts of the state due to the small and scattered population, he instituted an extensive redshirt program. Success was immediate with his 1962 squad going 9-2, and though it can be agreed upon that Oklahoma, which had dominated the Big Eight Conference since the mid-1940’s had taken a step back, Nebraska was legitimately in the mix for national recognition. He brought the Huskers to four consecutive Big Eight titles, five consecutive bowl games, and at least a top six national ranking from ’63 through ’66.

Devaney’s first team set the tone, as did Devaney himself. Perhaps it was an ill-advised statement relative to the probation that his Wyoming program was smacked with for illegal recruiting benefits in 1957, but the new head coach immediately stated, albeit in a humorous manner, “We don’t want to win enough to get on probation, just enough to be investigated.” Despite seven losing seasons, the Huskers had talent although the disappointing three-win 1961 season could be summarized with the statement, “Big team, but a really slow team.” Devaney’s philosophy was to keep them large but produce a bit faster bunch of tough guys. Fullback Bill “Thunder” Thornton had been All Conference in ’61, with halfback Rudy Johnson and quarterback Dennis Claridge showing signs of life. Huge for the day at 6’4” and 251 pounds, two-way tackle Robert Brown, who would later develop into the Hall of Famer known to the football public as the 280 pound “Boomer” Brown was quick enough to drop into pass coverage from a linebacker’s position or from the defensive line. The Cornhuskers 9-2 record was augmented by a 36-34 victory over Miami in the Gotham Bowl but was merely a prelude to Devaney’s presentation of “his kind of team” that took the field in 1963.

For better or worse, he had immediately set a very high standard. The ’62 team averaged thirty-two points per game, an increase from the eleven per game the previous season. The Huskers nine wins were well beyond the expectations of the most enthusiastic and optimistic followers and the initial call for the entire state to wear red, fill the stadium, and donate as little as one dollar per year to the program, created a groundswell of support and a bit of fan frenzy. Almost immediately erasing fan apathy with a bowl victory and national ranking, Devaney was the picture of the evangelical carrier of good news about his program as he criss-crossed the state forming booster club chapters and making all Nebraska residents feel as if they were part of the process. He received pledges from the newly established Husker Beef Club, a group of cattlemen, for donations of 200 butchered steers to provide prime meat for the squad. He encouraged red hats, red shirts, red pants, and red cowboy boots as haute couture for game day wear. In one season he managed to convince enough fans to travel to away games so that over time the sea of red in opponents’ stadiums altered the atmosphere of those contests. Kansas coach Pepper Rodgers told Devaney that the size of the crowds that followed them out of town to see their Huskers play, made him feel that the games at Kansas were much more like Nebraska home games.

The multiple offense, with

Rudy Johnson a national top

ten finisher in yards per

carry, had the country’s

best rushing offense, the

fifth best scoring offense,

and a total offensive count

that left them ranked at

number eight at the end of

the season. The Orange Bowl

victory over Auburn produced

a 10-1 finish with a

mid-season 17-13 loss to Air

Force as the only blemish.

Whoever viewed their Big

Eight title and Number Six

end-of-season ranking,

scratched their heads and

asked, “Where did they come

from?” wasn’t alone but the

Nebraska program had entered

a new dimension.

|

Ascension to the top of the Big Eight Conference was one matter, but Devaney and his staff traveled the nation seeking out players who would fit into the conservative social environment of Lincoln, Nebraska. Devaney’s folksy, down-home manner continued to win over players and parents even as the college cultural scene became radicalized. Nebraska games became the place to go for excellent football and an enjoyable Saturday afternoon. During the Devaney era, Memorial Stadium was expanded four times, enhancing seating from 30,000 to 76,000 and individuals began to bequeath their season tickets in their last will and testaments. Devaney was not the revered “X’s and O’s coach” that some were, or a legendary motivator in the mold of a Bear Bryant. He was a coach that players would go all out for and he had a knack for knowing what position would best suit a specific player’s skills. Through it all, he remained modest and by all accounts, witty and fun to be with. Typical was the story that made some of the religious followers of Husker football at first take a step back, with the conversation stated, “Is it true that you’ve sung ‘Bringing In The Sheaves’ to a player’s mother in order to get her son to come to Nebraska?” Devaney replied, “Yes, I did that. The mother came to Nebraska and the boy enrolled at Missouri.”

Devaney was one of

the first of the big

name, mid to

late-Sixties coaches

who did not have

rules regarding

length of hair,

facial hair, or

style of dress as

long as his players

obeyed the

university code of

conduct and

dedicated themselves

to the team effort.

His assistant

coaches were always

viewed as being

“accessible” and

Devaney himself had

an open door policy

that the players

took advantage of.

He knew that it was

important for his

players to feel as

if they were a part

of the campus

community and

allowed them to

behave like other

college students.

One player stated

that “The big thing

was the closeness.

The players got

along. No race

problems, no

nothing.” Devaney

went out of his way

to provide

second-chances to

players who deserved

it and pushed them

to both remain in

school and earn

their degrees.

|

The “First Act” of Devaney’s Nebraska dynasty lasted from 1962 through the ’66 season, with 9-2, 10-1, 9-2, 10-1, and 9-2 records. As Big Eight Champions Nebraska became major bowl game participants and although they lost the Cotton Bowl to Arkansas following the ’64 season and two consecutive bowl games to Alabama, one in the Orange Bowl and the 1966 season ending game in the Sugar Bowl, they were now a national player. Devaney had taken his initial “big but slow” squad and recruited it into a faster team but the bowl losses to the extremely quick Bama squads and to Arkansas indicated what the future would bring. Consecutive 6-4 seasons in 1967 and ’68 came from lackluster recruiting and the process of reshaping the aggressive, tough, and swarming type of group that Devaney envisioned. The ship would be righted for the final act of Devaney’s coaching career, one that placed him at the pinnacle of his profession.

Part 3 To

Follow: