C.R. ROBERTS, FORGOTTEN HERO ON AND OFF THE FIELD

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS May 2015:

C.R. ROBERTS, FORGOTTEN HERO ON AND OFF THE FIELD

By Dr. Ken

Younger fans have no clue and older fans have no doubt forgotten the exploits and impact of C.R. Roberts, a former University Of Southern California running back who later played in the Canadian Football League and then with the San Francisco Forty Niners for four seasons. There are perhaps more football fanatics that are familiar with his high school exploits than his USC career and some who remember only his name as part of the Forty Niners “Alphabet Backfield.” Yet Cornelius R. Roberts was a force within every community he ever lived, creating positive change and the advancement of not only race related civil rights, but more accurately, the rights for all.

In what was a storied high school career, Roberts’ exploits have, after more than sixty years, still left him as the First Team Halfback on the San Diego Area All Time High School Football Team.

|

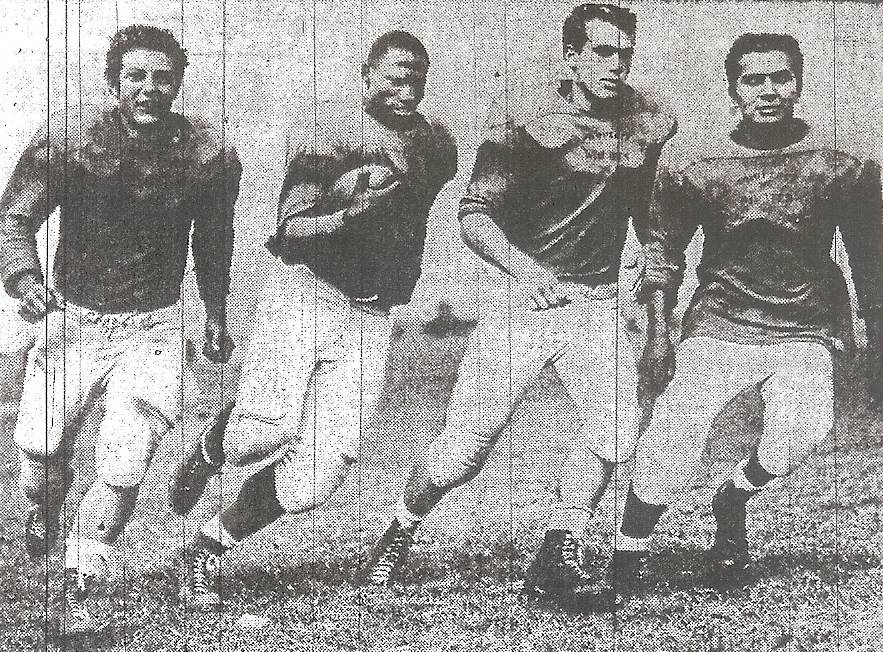

Roberts was truly a man among boys as a two-way high school football star

Roberts scored thirty-one touchdowns in the first eight games of his 1952 junior season at Oceanside Carlsbad Union High School. At 180 pounds he had the power to run through and over opponents, and the track speed to run around them. With Ronnie Knox earning the Helms Athletic Foundation California High School Player Of The Year award, Roberts 1599 rushing yards, eleven yards per carry average, and 181 points scored found him as the California Small School Player Of The Year. “Robot” to his teammates because “all they had to do was request a touchdown and he’d produce one…” and “The Oceanside Express” to those in the press, he returned in ’53 for his senior season at 200 pounds and accumulated statistics that cemented his place on the “all time” lists and made him both a High School All American and again the California Player Of The Year. In nine games, rarely playing their full length, Roberts rushed for 1903 yards with games that included running totals of 274, 331, and 317 yards. He passed for seven touchdowns while ten of his thirty TD’s came from sixty to eighty-six yards in length. He scored 187 points and rushed for a 9.5 per carry average. Seemingly too good to be true, he excelled as a top rated track and field athlete, was the President of his Sunday School class, maintained a B academic average, and was an Eagle Scout. Looking first towards the United States Military Academy, Roberts instead opted to attend college locally at USC.

He continued his track and

field activities as a

sprinter and long jumper,

defeating future Olympian

Rafer Johnson with a 24

feet, 3.5 inch long jump.

Established as a punishing

fullback who augmented the

exciting runs of halfback

“Jaguar Jon” Arnett, Roberts

caught national attention in

the opening game of his 1956

junior season against Texas.

With but three

African-American players on

the Trojans squad, Roberts

was the most visible and he

was always quick to note

that while the USC general

student body may not have

been supportive to

minorities on campus, his

teammates and coaches were.

In the past when playing in

the South or Southwest where

racial segregation was the

rule or state law, most

integrated teams would leave

their African-American

players at home. As

President of his USC

fraternity, Roberts had

already integrated

fraternity row and had been

instrumental in getting the

USC Student Senate to

approve the presence of

females on what had always

been the USC all-male

cheerleading squad. He had

no intention of missing the

season’s opener despite

being in violation of Texas

state law and the very real

danger he would face.

|

Neither university would agree to a cancellation of the game and from the perspective of Texas onlookers, the tension was ratcheted up when Roberts and his Black teammate stayed at a previously Whites-Only upscale hotel in Austin. Indicating that the experience in Alabama of USC’s Sam Cunningham which would follow a decade and a half later was really a sequel to his experience, Roberts later said, “I didn’t really get the picture” as his coaches tried to dissuade him from making the trip. “The coaches kept trying to tell me that the game was not that important. They tried to talk me out of traveling, saying we were going to win all the rest anyway.” He also clearly recalls intending to make a statement on the field, when given an opportunity. He noted “the greatest sense of satisfaction” he received when staying at the team hotel was having not only every African-American employee come to his room to congratulate him, but many residents from the city who would borrow one of the employee uniforms and sneak into the establishment, just to meet him and shake his hand. Roberts officially became the first African-American to participate in an athletic event against the University Of Texas within the state and although he played a scant twelve minutes, it was twelve minutes of pure hell for the Longhorns.

In those twelve minutes Roberts rushed for what became a long-standing school record of 251 yards and added three touchdowns to his personal beat down. It wasn’t until the opening game of the 1975 season that Ricky Bell eclipsed Roberts’ mark with a 256 yard performance against Duke. He put a tremendous hit on the Texas quarterback which very much incited the hostile and segregated crowd, bringing the staff’s decision to remove him from the game. The 44-20 victory kicked off a successful 8-2 season and his performance in the game made Roberts a national figure with All American mention. This event pushed him harder to correct what he believed were inequities and he returned to USC and was eventually successful in helping to gain approval for the first Black fraternity on the campus.

The entire 1956 season,

despite its success, was

unfortunately marred by the

scandal that affected the

major West Coast schools [

see HELMET HUT http://www.helmethut.com/College/USC/USC1956.html

]. With ambiguous rules

related to permissible

benefits and scholarship

eligibility, the entire

Pacific Coast Conference was

forced to reorganize by

1958. Many players, and

Roberts unfortunately one of

them, had to surrender up to

a year of eligibility.

Roberts chose to play what

would have been his senior

season at USC in the

Canadian Football League

instead, spending 1957 and

’58 with the Toronto

Argonauts. At the conclusion

of the ’58 collegiate season

when his USC graduating

class was eligible for the

National Football League

draft, he was a fourteenth

round pick of the New York

Giants. On July 8, 1959,

before his Giants career

began, Roberts was traded to

the Pittsburgh Steelers for

offensive guard Darrell Dess.

Steelers head coach Buddy

Parker was a prolific trader

and with bodies coming and

going, Roberts became

expendable and in

mid-September was released

and signed by the Forty

Niners prior to the season’s

final contest. He remained

with the Niners through the

1962 season, a contributor

at fullback rather than a

star in an offense loaded

with Pro Football Hall Of

Fame members Joe Perry, Hugh

McElhenny, and Y.A. Tittle,

J.D. Smith, R.C. Owens, John

Brodie, and before switching

to defense, the swift Abe

Woodson. One of Roberts

“best” contributions was his

inclusion in the 1960

backfield contingent that

gained the moniker “The

Alphabet Backfield” which

included Y.A. Tittle, R.C.

Owens, J.D. Smith, and

Roberts. At the conclusion

of the ’62 season, Roberts

returned to Canada and

played one more season with

the Hamilton Tiger Cats.

The end of his

professional

football career was

the true beginning

of his work that

contributed so much

to the communities

he lived and worked

in. All of the

ground breaking

efforts made at USC

were a prelude to a

lifetime of

improving the daily

existence of others.

He completed his

undergraduate degree

in Business

Administration from

USC and a Masters

Degree in

Educational

Administration from

Long Beach State; he

became the first

African-American

Loan Officer for

what was then a

segregated Bank Of

America; he

integrated the

Berkeley Board Of

Realtors; he was

instrumental in

securing housing

rights for

minorities in Los

Angeles. Roberts

spearheaded a drive

to incorporate the

city of Carson,

California and

became its first

Black mayor and then

was instrumental in

bringing the new

California State

University Dominguez

Hills campus to

Carson and making it

accessible for

moderate income

families. As the

holder of seven

teaching

certificates,

Roberts served as a

high school teacher

and administrator

for a number of

years. Perhaps

believing that he

was not doing

enough, he served as

the Transportation

Venue Assistant

Manager for the 1984

Olympic Games held

in and around Los

Angeles and as the

Vice President of

the Retired National

Football League

Players Association.

He has been chosen

to advise both

Congress and the

President’s office

on youth mentoring

and educational

projects and has

continued his work

in youth counseling

and with Christian

ministries. If this

seems to be an

ongoing and perhaps

never-ending list of

charitable and

community service

work, it almost is.

C.R. Roberts earned

a “name” as a

revered athlete and

then cashed it in

for the benefit of

his community. He

did this to an

extent that eclipsed

his time in the sun

as an athlete, for

the betterment of

many. As a

University Of

Southern California

alumnus, he is

revered by those at

USC for his work and

remains active in

all community and

university affairs.