CHARLIE POWELL, A TRUE ATHLETE

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS October 2014:

CHARLIE POWELL, A TRUE ATHLETE

By Dr. Ken

My usual explanation for some of

my family’s socially

unacceptable behavior was

usually “Don’t look at me, I was

taken in by the dopey Polacks.”

While some of Polish ethnicity

may be offended by the use of

the term Polack, my father’s

family was fiercely proud of the

fact that they were “off the

boat immigrants” who worked

their way up from the bottom.

They wore what was an ethnic

slur to some, as a badge of

honor. The men on that side of

the family were a tough group;

hard working, hard drinking,

hard gambling, and hard fighting

iron workers with a few having

reputations as less than model

citizens. There were as the old

man said, “One or two clinkers

in the bunch” but almost all

were law abiding in an era and

in neighborhoods where hard

drinking, hard gambling, and

hard fighting were seen less as

vices, than standard ways to

blow off frustration with a life

that by any measure, could be

difficult. Adding to my father’s

frustration was what he saw as

an interruption in what could

have been a successful athletic

career. Dropping out of school

after fifth grade to support a

married teenaged brother and his

family, my father’s only outlet

from jobs as an ice man,

mechanic, and iron worker was

the Industrial League basketball

games played between the

employees of various New York

City based enterprises. A small

stipend and side bets fueled

these rather competitive

contests and I at times heard

his refrain that was very much

the equivalent of Marlon

Brando’s famous On The

Waterfront, “I coulda’ been a

contender instead of a bum,

which is what I am, let’s face

it.” My father held a deep

seated belief that under

different circumstances, he

could have “been an athlete” and

the quality of athleticism was

cherished. Other than showing

off his still deadly, even into

his mid-forties, underhand foul

shooting and antiquated two-hand

set shot as he competed well

with twenty year olds on a local

basketball court, he focused his

athletic interest on baseball,

which was typical for the era.

He still however, maintained

enough awareness about football

to at least know who the Polish

standouts were, with Giants

tackle Dick Modzelewski a

favorite.

In baseball, the Brooklyn

Dodgers ruled because we lived

in Brooklyn, and the loyalty was

maintained after we moved. When

the Dodgers migrated to Los

Angeles, my father bailed out on

them but we knew that Johnny

Podres was to be exalted, not

just for his heroics in the 1955

World Series but because he was

Polish. Despite hating the

Yankees, we were told to root

for Tony Kubek because “He’s one

of us” as was Bill Skowron. Even

the players in far off cities

like Bill Mazerowski and Moe

Drabowsky were revered. The

highest praise however, was

accorded to “the athletes,” men

like Gene Conley who played both

Major League Baseball and

professional basketball. That he

did both for championship teams

was, to my father, the ultimate

achievement. In Brooklyn, we of

course knew “everything” about

Jackie Robinson and he too was

my father’s hero. He overcame

great odds to get and make the

most of his opportunity to play

and as my father reminded me,

“This guy can be a pro at a lot

of sports.” Because he was one

of the great names and a star we

actually saw on the streets at

times, as we did most of the

Dodgers, I studied his history.

Robinson’s football

accomplishments made it obvious

he truly could have achieved

greatness in any number of

athletic endeavors.

|

The Brooklyn Dodgers of baseball featured the great, ground breaking Jackie Robinson but only after he starred in football for UCLA

|

Powell graduated from San Diego High School as a multi-sport athlete who excelled in football, basketball, baseball, and track and field. Running hurdles and sprinting 100 yards in 9.6 seconds while also being the team’s shot putter certainly implied that he participated in both aspects of “track” and “field” and well reflected his athletic versatility. He had options, with offers from the Harlem Globetrotters, the St. Louis Browns baseball organization, and numerous college football scholarship offers. Notre Dame and the major powers of the western U.S. called for his services but he chose baseball. He left the St. Louis organization after a stint in the minor leagues, “bored” and missing football. He became the National Football League’s youngest player when he signed with the Forty Niners and immediately fought for a starting position as a 220 pound defensive end. From 1952 through ’57, Powell was relentless and though stout against the run, became what might have been the NFL’s first definitive pass-rush specialist. In a time that sacks were not recorded, he chased down and tackled Detroit Lions quarterback Bobby Layne behind the line of scrimmage ten times in one game.

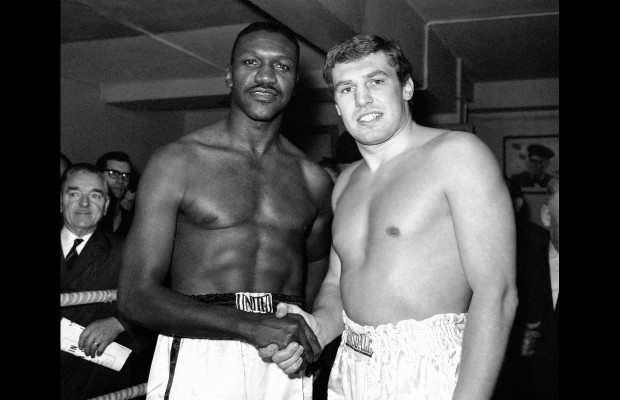

In the off seasons, Powell continued to indulge in his love of boxing. As a youth, he took boxing lessons from one of his neighbors, World Champion Archie Moore. Fighting regularly at the local boys’ club, Powell’s father once remarked that “they had to stop him because he was knocking too many guys out.” He became a professional in 1953 and with success, sat out the 1954 football season to focus on his boxing career. He returned to the Forty Niners in ’55 but continued to box in a very serious manner in the off seasons. After the 1957 season, he again decided to place his efforts into boxing and retired from professional football. Reducing his playing weight from 230 to a “fighting trim” of 210, he began to climb the heavyweight ranks. By 1959, having knocked out Nino Valdes, the second ranked heavyweight in the world, Powell found himself rated number four in the division As a boxing fan, my father knew his name but had no idea that Powell was also a professional football player. He was just a name in the newspapers or one of numerous fighters seen on occasion through the blur of our tiny black-and-white Dumont television set on the Friday Night Fight Show.

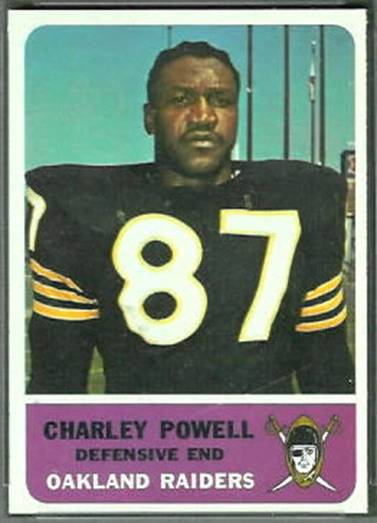

Powell, despite earning recognition as a developing heavyweight with world class potential, signed with the new American Football League in 1960. He was only briefly a member of the Los Angeles Chargers as they traded him to the Oakland Raiders prior to the start of the AFL’s inaugural season. As a Raider, Powell again was outstanding, especially as a pass rushing defensive end and remained with the team through their first two seasons, to again, spend more time on his boxing career.

Although Powell had originally

signed with the Los Angeles

Chargers when joining the AFL,

he was traded to the Raiders

before the league’s inaugural

1960 season began. At defensive

end wearing number 87, he

tormented his former team on

this play

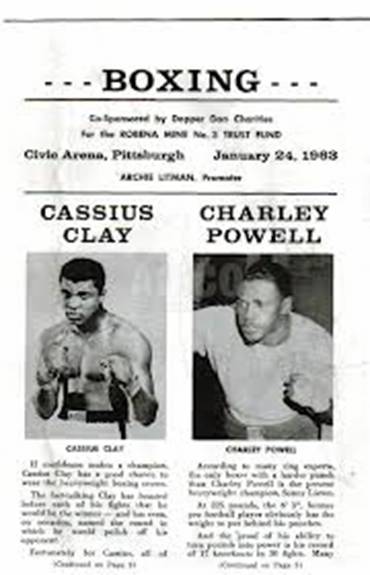

Powell caught my father’s

attention in a big way when the

announcement was made that

Charlie Powell (“Charley” in the

fight game) would box the

rapidly rising former Olympic

Champion Cassius Clay. My father

took note, stating that “Powell

must be better than we thought

if he’s fighting the Clay kid.”

The Clay Kid of course later

became Muhammad Ali and on

January 24, 1963, he kayoed

Powell in the third round, two

fights prior to defeating Sonny

Liston. Powell later lost to

former World Champion Floyd

Patterson but it was widely

agreed that had he followed a

more traditional boxing path,

Charlie Powell could have been a

true contender and top rated

heavyweight for quite some time.

Comparing his $12,000.00 purse

for the Clay fight and noting

that it was more than his salary

for any of his NFL or AFL

seasons, Powell may have

realized that boxing could have

been a more lucrative path for

him. His brother Art Powell, a

top AFL receiver primarily with

the Titans and Raiders,

explained it best by noting that

if managers and trainers had

“handled him right, he might’ve

been a champion.” Charlie was

often rushed into fights with

very good opponents rather than

given the opportunity to work

his way up through the ranks as

most fighters were, especially

in that era. He was a serious

fighter but for long stretches

of professional football camp

and then the actual seasons, he

was not on the boxing scene.

The well-known boxing trainer

Cus D’Amato who trained Floyd

Patterson and mentored a young

Mike Tyson, briefly worked with

Charlie in Catskill, N.Y. and

said, “This is a kid with great

ability and a tremendous punch,

but with a lot of bad habits. If

only you’d brought him to me

five years ago.” When he finally

retired from both sports, he

became a salesman in the

automotive and cleaning supply

businesses and owned a business

in South-Central Los Angeles.

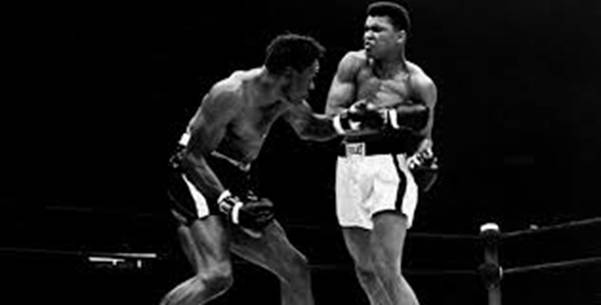

January 24, 1963, Charlie Powell

goes toe-to-toe with Cassius

Clay, but lost the fight on a

third round knockout

Unfortunately, and perhaps as a

result of football, boxing, or a

combination of both pursuits,

Charlie suffered from dementia

for a number of years prior to

his death. Brother Art said, “He

was losing his short-term

memory, but the long-term stuff,

he had that.” Much of the

“long-term stuff” included an

underrated and very good pro

football career and a boxing

career that saw him share the

ring with the higher rated

fighters of his era, including

Ali. A true all around athlete,

and obviously blessed with

favorable genetics as evidenced

by the career of brothers Art

and another younger brother

Jerry who played at Northridge

State and then as a receiver and

return man for the World

Football League Hawaiians in

1974, Charlie Powell was one of

the few who mined his talent and

rose to the top in two very

distinct athletic endeavors.

He was also proud of the fact

that as the oldest of nine

children, he had what he

believed was a wonderful life

and parental guidance. He at one

time stated “We weren’t rich,

but we had all the love and

attention in the world. There

were times when we had to pour

water instead of milk on our

Post Toasties, but there were

never any dope arrests in our

family and no one ever had a

child out of wedlock.” Men like

my father recognized great

athletic ability and “the right

type of upbringing” and it’s a

shame that more have not and

never did. Charlie Powell

deserved more.