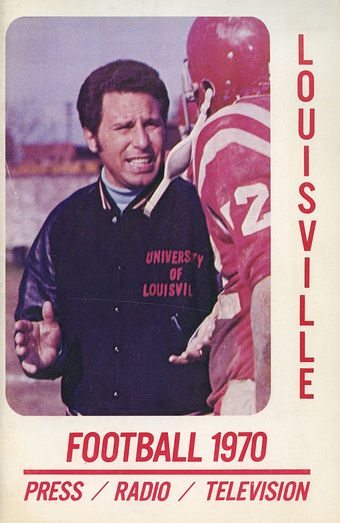

A LOOK AT LEE CORSO, THAT'S "COACH CORSO," AT LOUISVILLE

HELMET HUT NEWS/REFLECTIONS September 2014:

A LOOK AT LEE CORSO, THAT'S "COACH CORSO," AT LOUISVILLE

By Dr. Ken

One of my favorite football personalities is Lee Corso. Many HELMET HUT readers, while certainly familiar with Corso as a college football analyst and integral part of the ESPN College Game Day programming, were first made aware that Lee Corso was an outstanding collegiate football player after they read the seasonal summaries of our Florida State helmet display [ see HELMET HUT http://www.helmethut.com/College/FloridaState/FSindex.html ]. Our staff had as much fun as the international audience watching Corso don his 1955 Florida State uniform which included the authentic reproduction of his helmet that was provided to him and ESPN by HELMET HUT [ see http://helmethut.com/College/FloridaState/Corso.html ] on Game Day.

|

Lee Corso stood out as a quarterback and on defense

The helmet of course was beautiful and reminded fans “in the know” that Corso had overcome a modest socioeconomic background to star as a multi-sport athlete at Miami’s Andrew Jackson High School and then as the quarterback and school interception record setting defensive back of Florida State. What was also new information to many was the fact that Lee was an innovative college football coach, both as an offensive assistant and head coach, one who was influential in opening up the passing game wherever he applied his skills. He was popular with his players and fans and if nothing else, brought tremendous enthusiasm to the profession. The “wild and crazy” nature that he often if not always demonstrates on the College Game Day set is nothing new and not a television construct. Corso’s motto, admittedly borrowed from Ralph Waldo Emerson, is “Nothing was ever achieved without enthusiasm” and he applied it immediately as a coach. He was an ace recruiter as well as something of an offensive genius.

After serving his time as an

assistant at Maryland and the

U.S. Naval Academy, he became

the head coach at the University

of Louisville in 1969. Though

the news did not spread far from

the Louisville area, naming

Corso as the Cardinals head

coach produced major local

demonstrations. Protestors

filled the city streets, calling

upon the U of L administration

to hire Paulie Miller, one of

the most highly respected high

school coaches in the state.

Miller attained his status as

the head football coach of

Louisville’s Bishop Flaget High

School, establishing the program

as their inaugural coach in

1945, winning state

championships in 1949, 1952,

’58, and 1961, and developing

highly successful players, with

Paul Hornung and Howard

Schnellenberger perhaps the best

known. He coached at Flaget

through 1963 and was clearly the

people’s choice and on February

19, 1969, his supporters took to

the streets, loudly protesting

the hiring of anyone but Miller.

Paulie Miller’s supporters

filled the streets of

Louisville, demanding that

he be named the Cardinals

new head coach

Corso was a thirty-three year

old unknown while Miller was a

local legend. The pressure was

on Corso immediately, even at

Louisville where the program was

typically “middle of the road”

with the addition of a few nine

win seasons and a few one or two

win seasons under head coach

Frank Camp who had held the

reins from 1946 through ’68.

While there had been an

occasional star, like the

Chicago Bears linebacker Doug

Buffone, there was never a lot

to cheer about or make the

stadium a definitive destination

on a Fall Saturday afternoon.

There was pressure too from the

school administration with some

believing that a lack of revenue

and poor attendance could soon

lead to the program either

cutting back to “small college”

level, or being dropped

completely. The message was

clear, “Win and fill the seats!

Do it now.”

If nothing else, Corso was

immediately fun and as Sports

Illustrated noted during the

1970 season, Lee “was coaching

at Louisville and making a name

for himself by 1) coaching good

and 2) having fun, a

contradiction in terms by most

accepted coaching tenets.” He

did a lot of fourth down

gambling, literally waved the

white towel from the sideline

against Memphis State in a 69 –

19 blowout loss, marched a

turkey onto the field for the

pre-game coin toss and captain’s

meeting for a Thanksgiving day

clash against Tulsa, and rode an

elephant through the streets of

the city. He recruited well,

bringing in Tom Jackson from

John Adams High School in

Cleveland and quarterback John

Madeya who would throw for more

than 4500 yards before he

graduated.

Louisville QB John Madeya

became a record setter under

Coach Corso

Corso’s 5-4-1 mark in ’69 jumped

to 8-3-1 the following season

and it was obvious that his team

liked their head coach and was

playing hard for him and the

staff. He hosted “Italian

Nights” at the training table,

complete with checkered

tablecloths, candles, and a menu

that included pasta, garlic

bread, and spumoni. They enjoyed

their “hip” and modernized

pre-game warm up routines, eye

catching enough to have the

Georgia Tech staff ask for

advice. Of course, Corso quipped

that he would have been happier

if Tech had been interested in

asking for his football plays.

He solicited walk-ons and was

rewarded with Scott Marcus, a

bearded, long-haired hippie type

who was given a full scholarship

for his exceptional punting

ability.

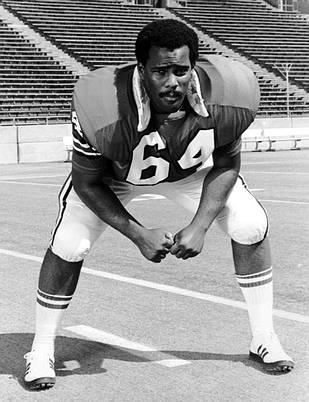

Behind the antics was a lot of

very good coaching. Corso’s eye

for talent where others did not

see it held him in good stead.

Tom Jackson was listed as 5’11”

and 220 pounds but according to

Corso, was closer to 5’8”,

perhaps a bit of an

exaggeration. Still, Jackson was

not highly sought by other

collegiate programs because he

was considered to be “too

small,” but Corso saw a hitting

machine, a player that “had

fantastic quickness” and

strength and most importantly,

“He just never missed. He never

missed a guy. Those guys at Ohio

State, Gradishar, Cousineau, and

some of those others at

Michigan, they were good, but

this guy (Jackson) was better

than any of them.” At

Louisville, Jackson was a

three-time All Missouri

Conference selection, two-time

MVC Player Of The Year, and led

the team in tackles in each of

his three varsity seasons,

eventually having his number

retired. He went on to a highly

successful fourteen year career

with the Denver Broncos, winning

All Pro honors four times and

later became a popular ESPN

football analyst and

commentator.

Coach Corso greets star

linebacker Tom Jackson as he

leaves the field. The Cardinals

wore an American flag decal

during a period of time when

flying the flag was not popular

on many college campuses

Although riding an elephant and

bringing a turkey onto the field

for the coin toss can be seen as

gimmicks designed to attract

attention and fans, Corso’s

coaching knowledge, teaching

ability, and dedication to old

fashioned values and the

fundamentals of the game were

real. He affixed American flag

decals to both sides of the

white helmet during a time of

social strife, anti-war

protests, and anti-government

sentiment. While often burning

the country’s flag on campus was

viewed as an acceptable form of

protected speech and anything

staunchly supporting “The

Establishment” was viewed as

“square,” and unacceptable by

college aged students, Corso had

his team display the flag as

part of the uniform “to

symbolize what I have been

trying to teach the kids:

teamwork, unity, pride,

dedication, and respect.”

Whatever values Corso taught,

they were accepted by his squad.

The 1969 team posted a 5-4-1

record with improvement to

8-3-1, the Missouri Valley

Conference Championship in ’70

and a 24-24 tie with Long Beach

State in the Pasadena Bowl. 1971

produced a solid 6-3-1 result

and in Corso’s final season in

’72, they rolled to a 9-1

performance, losing only to

Tulsa by a margin of 28-26.

The hard work that Corso put

into the Cardinals program paid

off not only on the field, but

in the stands. From the day he

arrived in Louisville, he

accepted speaking engagements

anywhere and everywhere within

the borders of the Bluegrass

State. He was an exceptionally

entertaining and informative

speaker, much as he is on

television and he gave everyone

in attendance his all. He

humorously described one early

morning, pre-7 AM talk to a

booster group that drew a total

of four individuals, and when

asked he responded, “Not four

hundred, four. One, two, three,

four. Gave ‘em a hell of a

speech too. The whole load.”

This was typical Corso,

enthused, pumped up, ready to go

at 110 miles per hour and from

1969 through 1972, doing it for

the Louisville football program.

At that point his record as a

head coach was 28-11-3 and he

finished ’72 with a national

ranking of eighteen, and as is

said in the music industry when

a song is rocketing for the top,

“with a bullet.” No one doubted

that there were bright days

ahead for Louisville football

and what had been a program

under consideration for

termination saw attendance

literally quadruple while Corso

was in charge, and now had plans

for a new football stadium. Not

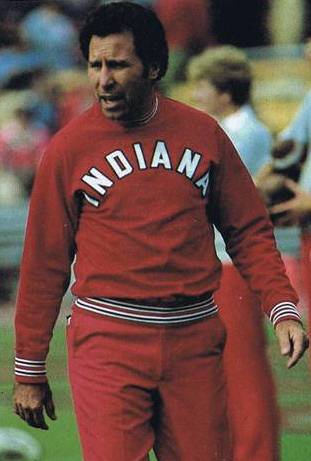

surprisingly, Lee Corso

attracted the attention of

other, larger programs and he

became the head coach at the

University of Indiana following

the ’72 season, a post he would

hold through 1982 before going

on to the USFL, Northern

Illinois, and ultimately

becoming a college football icon

on ESPN.

Lee Corso From a Personal

Perspective:

As a high school football

coach, I prided myself on

going the “extra mile” when

attempting to place young

men into an appropriate

college program. I was

blessed with an arrangement

where Co-Coach Joe Tuths, a

former Columbia University

center [ see

HELMET HUT NEWS

of August 2007

http://www.helmethut.com/Features/Dr.Ken46.html

]

and fellow Atlantic Coast

Football League Westchester

Bulls teammate, and I worked

hand in hand at Malverne

High School. Joe was a much

better Xs and Os coach than

I was and we both had very

good rapport with the boys

we coached. I was the point

man with college recruiters

and worked hard to make as

many meaningful contacts as

possible. At the time I

contacted Coach Corso, I was

no longer a full time

teacher or coach but jumped

in to assist one of the

players Joe and I liked so

much.

William “Bill” Jones was a 6’4”,

255 pound two-way tackle that

also threw the shotput and ran

high hurdles for our small

school. It was not unusual for

any of our athletes to

participate in two or more

sports but it was unusual to

have a young man who could

compete successfully in the

hurdles at Bill’s size. Despite

severe vision limitations, he

was an excellent student and

football player although as Alex

Karras once described playing

with his visual impairment, Bill

also had to “play body Braille

when tackling anyone.” We could

not afford the proper corrective

glasses or goggles leaving Bill

to play high school football as

he said, “almost blind.” This

did not prevent Bill’s final

college choices to come down to

Iowa and Duke. Heeding our

admonition to always get the

best college education possible,

especially with Joe as an Ivy

League graduate, Bill chose

Duke, politely thanking Iowa and

the other twenty or so schools

that had made scholarship offers

or overtures to him. A few

weeks after the colleges had

fielded their officially

accepted offers and freshman

rosters were completed, Bill

visited the Duke campus and

called my home, telling me how

well his visit was going, how

unlike his first group

recruiting visit, he now had

time to talk individually with

faculty from the department of

his projected major, and how

nice the staff was.

Unfortunately, I received

another phone call from Bill at

approximately 2 AM Sunday

morning, explaining that he

would not attend Duke because he

had gone to dinner with one of

the assistant coaches and while

waiting for a table in a “nice”

restaurant, he was taunted and

ultimately engaged in a

fistfight, along with the Duke

assistant, because a group of

men continued to direct racial

epithets towards him. A knife

was pulled, Bill and the Duke

coach fought successfully in

their own defense and thankfully

he was uninjured but the real

damage had been done. Even

though the Duke coach literally

fought hard to defend Bill , and

despite my explanation that he

should not judge a university

that would provide an absolutely

wonderful education and football

experience by the actions of a

few moronic racists, he told me

he would not ever return to “the

South.”

At 6 AM that morning, a Sunday

morning, I called the Indiana

football office. In the days

before answering machines, I was

not certain what to expect but

hoped to have a custodian answer

the phone so I could leave a

message for Coach Corso. I am

sure that my shock and surprise

were palpable as Coach Corso

himself answered the phone. His

energy was obvious as he

explained that he was doing work

before going to church and would

be back in his office later in

the day. I explained Bill’s

situation, that I was quite sure

that the Iowa scholarship had

been given to another player,

and that he was a deserving

youngster. Coach Corso said that

he had but one scholarship

remaining only because another

player had to give up football

due to medical reasons. Having

never met me, without knowing me

as an individual or a coach, and

without checking references, he

said, and I can recall this as

if the conversation occurred

yesterday, “I’ll have a ticket

waiting for him at JFK Airport

on the first flight out here

tomorrow. Put him on the plane

with a few cans of film under

his arm, we’ll evaluate him

while we give him a tour of the

campus, and see if we agree with

your assessment.” Wow, what a

break for this student-athlete

who otherwise would not be able

to attend college. In the

mid-afternoon I received a phone

call from Coach Corso, who said,

“Hey Coach, thank you, thank

you, thank you. We’re going to

get him the proper eye glasses

so he can see what he’s hitting

on the field, although he did a

great job without the glasses,

we’re going to give him some

speech remediation, we hooked

him up with two professors in

the area he wants to study, and

we want him.” I asked, “Just

like that?” Corso’s response was

“Yeah, why not? He can play

exactly as you said he could, he

is just a great kid, his

transcript is wonderful, his

test scores are high,

absolutely, he’s our kind of

kid.”

Bill played for Indiana,

graduated, and settled in the

state while establishing his own

business. I have in the decades

since, dealt with literally

hundreds if not thousands of

coaches through my own work and

because I have two sons coaching

in the NFL and to this day, Lee

Corso’s kindness and absolutely

straight forward manner has

remained one of my best

memories.