Like many other football programs, the Illinois team was dismantled by

the need for manpower in the military during World War II. Called the

"Vanishing Illini", they were hit perhaps harder than most of the visible

programs. When the War ended, many of the players who had gone to battle,

some directly from college, others who had received military training on

other college campuses where they represented those schools on the field

before heading off to combat, returned to play at Illinois. These were

tough men; Art Dufelmeier had spent eleven months in a German POW camp;

Alex Agase was an All American at Purdue in 1943 and a Marine squad leader

who won a Purple Heart and Bronze Star for heroism on Okinawa; Claude

"Buddy" Young had served with the Navy in California. Young was offered

the opportunity to remain on the West Coast and play for UCLA but like the

others, returned to Illinois. Perry Moss was allowed to transfer from

Tulsa and huge 270-pound lineman Les Bingaman was back. Coach Ray Eliot, a

former star for Coach Bob Zuppke's Illinois teams from 1928 through '32

followed in his mentor's footsteps, taking the head job from the master in

1942. He was excited about the '46 squad but like most other coaches who

welcomed back a bevy of War vets, had no idea what to expect. Losing early

to Notre Dame and Indiana, Eliot actually submitted his resignation but

the administration wouldn't accept it. The players received the message

loud and clear and the Illini fought through the remainder of the

schedule, winning with grit and determination. QB Moss and HB Young

provided the fireworks and All American guard Agase won the same acclaim

he had when he was "on loan" to Purdue in 1943. The team received the Rose

Bowl bid as underdogs to UCLA. The 45-14 dismantling of the Bruins was a

shock to the football world. The passing combo of Moss to end Ike Owens,

the speedy dashes of Young, and the line play of Agase at guard and

Bingaman at tackle overwhelmed the surprised UCLAN. The West Coast media

had clamored for Army to play their champion but this one game established

Midwest football as "the real deal" in the first year of the Rose Bowl

conference contract. Claude "Buddy" Young only had two years of college

football, both with Illinois but in 1944, he broke a number of records

held by the immortal Red Grange, scoring 13 TD's and averaging 8.9 yards

per carry. He duplicated those heroics in '46, becoming a member of the

College Football Hall Of Fame, and then took his 5'5", 163-pound frame to

the pro ranks, playing nine seasons, first for New York in the AAFC and

then Dallas-Baltimore in the NFL. He averaged over 1000 yards per season,

gaining 9419 yards in nine seasons of play and later serving with

distinction in the Commissioner's office. Eliot adopted the Riddell RT

plastic helmets with a burnt orange shell and dark navy blue one-inch

center stripe for his players, a combination they would maintain through

the 1956 season. The addition of one-inch "Eagle style" gold numbers

trimmed in black on the rear of the helmet gave the headgear a finished

look.

Expecting to challenge again for the Big Ten title in '47, the team

fell off a bit to a 5-3-1 record, no doubt due to the loss of some of the

stars of the Rose Bowl squad of '46, especially Young and Alex Agase who

played for Chicago and Cleveland of the AAFC. Bingaman, who controlled the

middle of the line of scrimmage with his 270-pounds, had another solid

season and became one of the first "big men" in pro football, playing for

the Lions from '48 through their dominant seasons, to 1954. With all of

the War vets gone and the stars of the Rose Bowl season but a memory,

Eliot's 1948 team struggled to a 3-6 mark, beating only Purdue and Iowa

in-conference. Recruiting however, was good, with some of the frosh

earmarked for starting positions in 1949. The '49 record was also

disappointing at 3-4-2 as Eliot began to stockpile obvious talent. Young

Chuck Studley took over at guard, teaming with a tough Leo Cahill. John

Karras immediately took a starting RB spot, putting in a great 826 yards

on the ground. 1950 marked a return to prominence but with the Big Ten

title all but sealed, the Illini dropped the finale to Northwestern 14-7,

leaving them with a 7-2 record and blew the Rose Bowl bid. The play-makers

were on board; conference rushing leader FB Dick Raklovits, All American

Bill Vohaska, lineman Leo Cahill who went on to be a legendary coach and

GM in the CFL and World Football League, and potent HB Johnny Karras who

had run for more than 1400 yards in his first two seasons. In 1951 Karras

lived up to his billing as the finest back to play for Illinois since Red

Grange, a consensus All American who paced the running game with 658

yards, and led the team to a 9-0-1 record and the Big Ten championship.

The trip to the Rose Bowl led to a 40-7 rout of Stanford. With Bowl game

hero FB Bill Tate and QB Tommy O'Connell who transferred from Notre Dame,

the attack was relentless with only a 0-0 tie against the Buckeyes marring

the season's slate. The line was led by Charles Studley, a former Navy

submarine torpedo operator who went on to a sterling coaching career as

the head man at UMass, Cincinnati, the Houston Oilers, and the

D-coordinator with the Dolphins, Forty-Niners, and Bengals during the

glory years of each of those teams.

QB O'Connell had a big year in '52, tossing for 1761 yards, forty-five

of those to ends Rocky Ryan who piled up 714 yards and five TD's, and Rex

Smith. FB Tate was effective. Unfortunately even with safety Al Brosky,

the team could muster no more than a 4-5 mark. There was a quick 7-1-1

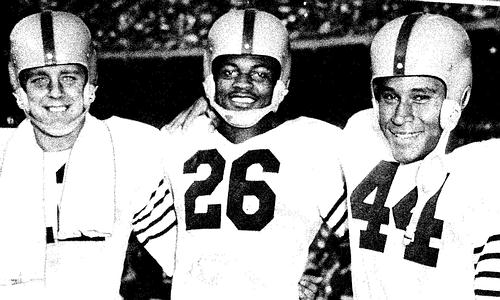

revival in 1953 with the debut of rookie backs "Mr. Zoom" (J.C. Caroline

from South Carolina) and "Mr. Boom" (halfback Mickey Bates). The

re-introduction of one-platoon ball played well for the Illini and when

the two soph backs first played an entire game together, the result was a

41-20 thrashing of Ohio State and 432 yards rushing, Caroline with 192 of

those and Bates notching four TD's! All American as a soph, Caroline led

the nation in rushing with 1256 yards and punted well. Bates was the team

scoring leader. A tie with new conference member Michigan State for the

title sent the Spartans to the Rose Bowl in a vote of Big Ten reps. With

the addition of hurdler Abe Woodson to the backfield mix of Caroline and

Bates, hope was high for a great '54 season but the absence of good line

play sent Illinois from the penthouse to the outhouse in one season, with

their 1-8 record a shocker. Caroline played well with an absence of

recognition but Bates was not as effective running from fullback.

The Illini battled back to respectability with a 5-3-1 record in '55,

still trying to tack together a decent line but stocking up on a bevy of

backfield talent. Joining Caroline, Bates, and Woodson, who was better

defensively, were soph fullback Raymond Nitschke and speed-demon Bobby

Mitchell. Mitchell gained 504 yards with a flashy 8.3 yards per carry.

Nitschke would be an obvious tough-guy, refusing to come off the field

after getting his teeth knocked out against Ohio State and telling Coach

Eliot, "Let me back in, they can't hurt me any more, I've already lost my

smile." Caroline departed for a ten-year career as a two-way back with the

Bears. There was more talent than 1956's 2-5-2 record reflected with QB an

ongoing problem. Tom Haller lettered as a back-up but proved to be a

better baseball player, lasting ten years in the Majors, mostly with the

Giants. Mitchell lost time to injury, leaving Woodson and Nitschke as the

workhorse backs. The highlight was an upset win over Michigan State 20-13

while the Spartans were ranked the best in the nation.