A book could, and perhaps should be written about the life of Curtis

McClinton. A legend in his hometown of Wichita, Kansas for his football

prowess, political activism, role in community affairs, and setting a

positive example for others to follow, his stature was built on

achievement. An academic and athletic standout at Wichita North High

School, he utilized his All Big Eight hurdler’s speed and agility as a

three-time All Conference fullback at Kansas University, was named to a

number of All American teams as a senior, and is in the Kansas Hall Of

Fame. He is a member of the KU All Time Team and played a productive and

award winning eight year career with the Dallas Texans – Kansas City

Chiefs in the American Football League. He was 1962’s Rookie Of The

Year, a three-time AFL All Star, and was later inducted to the Missouri

Sports Hall Of Fame. He earned undergraduate, masters, and doctorate

degrees, served in the federal Senior Executive Service under two U.S.

Presidents, graduated from Harvard University’s Kennedy School Of

Government, was the Deputy Mayor For Economic Development in Washington,

D.C., was a calming and active influence during the race riots of 1968,

and became a successful businessman in Kansas City. By every measure,

Curtis McClinton was a success.

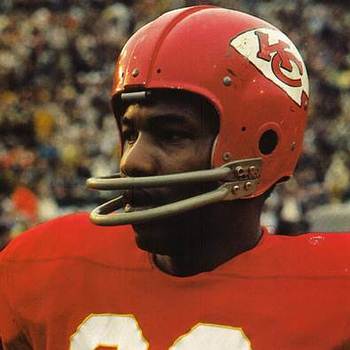

His excellent and versatile play allowed him to stand out

as a rusher and receiver for the first six seasons of his career, before

moving to tight end in 1968. During his time as the Chiefs AFL All Star

running back and exceptional backfield blocker, one that earned him the

Most Valuable Player Award in the AFL All Star Game following his rookie

season, his helmet featured both a two bar face mask, and later, the two

bar mask with the addition of a U-bar.

Throughout his career, McClinton had been the ultimate

team player. He was, with the great Abner Haynes, the central focus of

the Texans-Chiefs rushing attack in 1962 and ’63, serving as a potent

blocker for Haynes. In 1964 his productivity fell off, with blocking his

primary forte, only because Haynes was still effective and Southern

University rookie Mack Lee Hill showed exceptional potential. With the

death of Hill during the week preceding the final game of the ’65

season, McClinton again assumed a more prominent role in the Chiefs 1966

Super Bowl I year. By the start of the 1968 season a number of younger

backs had supplanted McClinton as the Chiefs primary rushing threat and

he had no difficulty in his role as a blocking back or special teams

player. As an All Everything end in high school and always an effective

receiver coming out of the backfield, Head Coach Hank Stram also

utilized McClinton at tight end. In part, the move was made to help both

McClinton and the team.

On August 10, 1968, the Chiefs defeated the Vikings 13 -

10 in their pre-season contest. During the game, McClinton suffered a

broken cheekbone, an injury noted in the newspaper articles following

the game. Attempting to return for the third game of the regular season,

he reinjured the cheekbone on September 22 against the Broncos and once

again, the injury was widely and publicly reported. During the 1968

season, McClinton missed a total of five games, presumably due to this

specific injury and when he returned, he spent most of his on-field time

at the tight end position. In order to better protect the area, Chiefs

equipment manager Bobby Yarborough, long known for his innovative

attempts to provide the highest level of player safety, the introduction

of the Dungard face masks to the squad, and the “homemade” external

padding on the surface of middle linebacker Willie Lanier’s helmet,

reconfigured McClinton’s face mask design. Experimenting with face mask

placement and combinations was “old hat” for Yarborough. His use of

additional one bar masks and their spacing had been used for years in

order to better protect Len Dawson, Fred Williamson, Sherrill Headrick,

Otis Taylor, and others from potential injury or the exacerbation of

existing damage.

McClinton’s injury received the similar “Yarborough

Treatment” with the fabrication of “strips” of single metal bars that

were then dipped in rubber and then red paint. The vivid red color marks

this specific mask as a precursor to the variously colored dipped face

masks that made their appearance in the NFL and World Football League in

1974. This very innovative alteration was initially applied to one side

of the helmet to protect the broken cheekbone and as McClinton revealed

in a recent interview, what was essentially “another faceguard on my

cheekbone, to provide greater protection and spread the force of the

blow” caused the helmet to fit in an unbalanced manner. McClinton

continued, noting “Originally, they just had it on one side. But when I

got hit, the helmet would end up leaning to that side and would often

come off, even though I was wearing a chinstrap, because it was heavier

on that side, the side with the extra faceguard. So they put it on the

other side to help balance the helmet, so it wouldn’t be heavier on one

side. We also thought it would be good to put it on both sides so the

opposing team wouldn’t know which side I’d been injured on. In other

words, it wouldn’t be as much of a target.”

The date that McClinton’s altered helmet made its debut

has never been confirmed although there is photographic evidence that it

was worn during the 1969 season and in Super Bowl IV. There is no doubt

that McClinton wore this protective innovation only after his cheekbone

fracture, or re-fracture of September 22, 1968. Approaching the 1968

season, Stram made a number of significant changes to the Chiefs roster

that saw the release or trades of a number of long time Chiefs and

shifted the playing position of others. McClinton however, entered the

season at his customary running back position, although he knew he would

be blocking more and running less with the emergence of Mike Garrett,

Robert “Tank” Holmes, and Wendell Hayes. It was not until after his

injury that he split time between the fullback and tight end positions.

Entering ‘69’s training camp, Stram had more changes in

mind, hoping to capitalize on the fine 12-2 mark of 1968. Two planned

upon changes were a permanent move to tight end for McClinton and

utilizing their great tight end Fred Arbanas, nearing the twilight of

his career, at offensive tackle. Once camp began, Arbanas demonstrated

that whatever had made him a six time All AFL selection and the tight

end on the All Time AFL Team, was still present and he both began and

ended the ’69 season as the Chiefs starting tight end. McClinton

remained the back-up and as he noted further in his recent interview,

“One thing about the injury is that it ended up changing the position I

played. I stayed in the backfield for a while, but then I went to

playing defense — I was a strong safety. Part of that was so that to

protect my head and my eyes. It enhanced my career, because I was

hitting, rather than being hit.” While McClinton was never officially

listed within any legitimate National Football League or AFL source as a

defensive player, there is little question that this ultimate team

player would have been willing to play as many and whatever positions

the Chiefs needed him to, including tight end, strong safety, and

special teams participant. As unusual and unique as this spectacular

helmet is, some mystery surrounds it. Mr. McClinton insists that his

injury was the result of a confrontation with Fred “The Hammer”

Williamson. There is no doubt that McClinton’s cheekbone injury occurred

on August 10, 1968 in the exhibition game versus the Vikings. There is

no doubt that his re-injury came in the third regular season game of

1968 against the Broncos. The newspaper reports are clear and

irrefutable. Every seasonal summary for ’68 indicates that McClinton did

not participate in five full games. However, any confrontation with “The

Hammer” occurred before 1968 because Williamson was released after the

1967 season and not resigned by any other AFL or NFL squad. Williamson

began his professional career with the Steelers in 1960 and then played

as a defensive back with the Oakland Raiders from 1961 through the ’64

season. He built his reputation with a purposeful self-aggrandizing

campaign that included his declaration that “The Hammer,” his

clothesline swiping forearm aimed at the head and/or neck of opponents,

was part of his game and a distinguishing feature. Most opponents viewed

the maneuver as dirty, beyond the rules, and a “cheap shot” meant to

injure. Mr. McClinton maintains that his cheekbone injury was a result

of a Williamson forearm blow.

McClinton dates the injury to 1964, Williamson’s final

season with the Raiders and before he was coincidentally traded to the

Chiefs prior to the ’65 season, for fellow defensive back Dave Grayson.

McClinton describes the helmet facemask change and injury by stating,

“That was the follow-up on the basic medical protection of my cheekbone.

My cheekbone was broken and I had an orbital blowout, which means my

eyeball came all the way out of the structure of my face and just kind

of hung there. There was a guy by the name of Fred Williamson, they

called him the Hammer, and he brought the hammer down on me. The way he

played was very, very detrimental, both to players and to the game

itself. He was a thug, to be quite frank about it, in terms of hitting

players in order to hurt them, not just to bring them down. It’s a rough

game, a game of hitting — that’s why you’re on the field. But there are

rules and regulations, and he deviated from that, and he did it with

cruelty and intent to injure.” In ’64, the Raiders and Chiefs faced off

on September 27th in Oakland and on November 8 in Kansas

City. Although the dissemination of news was much more limited in 1964

than it would be even four or five years later, there are no reports of

a McClinton injury or cheekbone fracture. The severity of the injury as

described by McClinton relative to his orbital damage, certainly would

have predicted his absence for at least one or two games, yet the

individual game results and statistics from the ’64 season indicate that

he played in every game, including those following both confrontations

against the Raiders and Williamson.

In 1964 McClinton did add the U bar to his usually worn

two bar mask and certainly that could be the additional though minimal

facial protection necessary to prevent further damage to an eye or

cheekbone. However, the timeline does not give clarity. With Williamson

joining the Chiefs from 1965 through 1967, it is possible that both he

and McClinton sparred during camp and practice and enmity was

established, but McClinton’s uninterrupted participation from his rookie

season of 1962 and in ’63 and ’64 when any game versus the Raiders

included a possible confrontation with Williamson, casts doubt on the

timing of such a devastating injury. Williamson was released from the

Chiefs prior to the ’68 pre-season and attempted to extend his football

career with Montreal of the CFL so the August 1968 injury was not

perpetrated by him. Of course, one would think that McClinton and any

other player would know with certainty who dealt such a telling and

injurious blow which leads us to perhaps one other possible conclusion.

In the mid-1990s, one of the NFL teams reported that

their star offensive player had received a broken jaw during a

hard-fought game against a team that had a defensive player that carried

a reputation of one who took the rules of contact right to their limit.

The official cause of injury was laid at the feet of this one defensive

player on a specific play. However, the truth was that the offensive

player had been injured in a mid-week brawl with one of his teammates

during a heated practice argument. The jaw was broken, never officially

reported, and the star played, at least into the second quarter of that

week’s game. Perhaps an initial cheekbone injury suffered by Mr.

McClinton was in fact caused by Williamson but not when he was with the

Raiders but instead, when he was one of McClinton’s Chiefs’ teammates!

Whatever the truth might be, the beautiful and innovative

Kansas City Chiefs helmet worn by Curtis McClinton during the 1969

season, and perhaps first seen in ’68, is a wonderful part of helmet

history.